Excavation of Bamburgh Castle Provides a Picture of Life in Northumbria

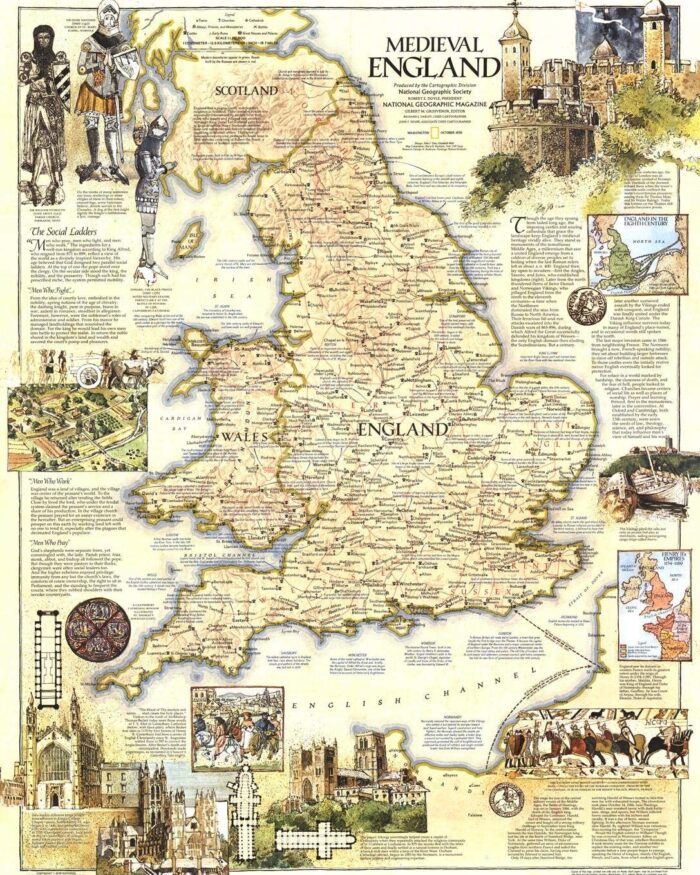

Briton in about the Year 802

Before we continue, let us travel from Mercia and points south to Northumbria. Remember that when the Romans abandoned Britain in the early fifth century, the Germanic Angle, Saxon, and Jute tribes, collectively called Anglo Saxons, took advantage of the power vacuum, and sailed across the North Sea to settle in England. Much of what we know about that period comes from The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, written by the Venerable Bede, (672-735) known as the “Father of English History.” Interestingly, Venerable Bede had the inside scoop on Northumbria because he lived his life there. He often mentioned Bamburgh as the kingdom’s ‘royal city’ in his writings. Reading about Northumbria’s history at the Bamburgh Research Project website, we learn that Northumbria produced many notable scholars, among them the monk Bede, who was born in Monkwearmouth in Sunderland. He joined the monastery at Jarrow in 681 AD aged 9. Jarrow became famous for its manuscripts and Bede spent much of his life translating the Bible from Latin into Anglo Saxon English. He progressed to writing a history of the English Church, and a life of Saint Cuthbert. His works added much to our knowledge of the origins of Anglo Saxon England. His magnificent work of scholarship, “The Ecclesiastical History of the English People” became the equivalent of an early medieval bestseller. In his time, Bamburgh was the nucleus of Northumbrian power, a keystone for maintaining dominance in this area of the British Isles.

History of Northumbria and Bamburgh Castle

Bamburgh Castle, Northumbria

Bamburgh Castle or “The Fortress by The Sea” is located on an outcrop of basalt rock on the Northumbrian coast of northern England. The outcrop of rock forms a long ridge and stands over one hundred feet over the surrounding land overlooking a natural harbor. Archaeological evidence indicates that this castle was once a fortress and existed long before the medieval period, but its written history and current name started with the Anglo Saxons.

| Ida the Flamebearer and first of the Anglo Saxon Kings of Bernicia lay the first timbers of a fortified wooden stockade and the original stronghold of Bamburgh Castle. When Ida died, King Aethelfrith took over Bamburgh. Aethelfrith’s children Oswald and Oswi were educated and baptized by monks in Iona. |

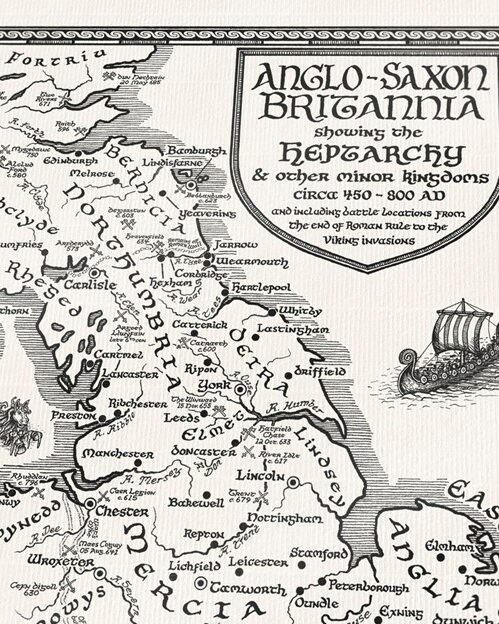

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us that in 547, an Angle warlord known as Ida the Flamebearer seized the Briton coastal fortress and the land around it and founded a kingdom called Bernicia. His grandson Æthelfrith brought that area and the neighboring Anglian realm of Deira under his dominion around 604, creating the unified kingdom of Northumbria. Æthelfrith gave the coastal fortress and the settlement around it to his wife Bebba, naming it Bebbanburgh. Protected settlements such as this were known as burghs and were designed to provide a safe haven for communities under attack. They became increasingly popular as Viking raids multiplied in later centuries. Eventually Bebbanburgh became Bamburgh. For the next centuries it played a significant role in English history, with its throne often changing hands between warrior kings. One such king was Oswald, the first Christian King of Northumbria.

Oswald was born in 604 AD to Æthelfrith but had to flee to the Scottish Kingdom of Dal Riata with his mother Acha, brother Oswiu and other siblings when Raewald of East Anglia came to power. It was in Dal Riata that he earned his nickname Lamnguin (meaning White Blade), an Irish epithet he earned while fighting for the King of Dal Riata.

It was his youth in the service of the Christian King Eochaid of Dal Riata that shaped the future of Oswald. His tutelage at the famed monastery on Iona would lead to Oswald’s fervent Christianity that would forever change the course of English history when he came to the Northumbrian throne at the age of thirty.

Oswald established himself as ruler of a united Northumbria in 634. He was recognized as Bretwalda and according to Bede’s account, he “brought under his dominion all the nations and provinces of Britain.” He sent for monks from Iona to set about the conversion of his people to Christianity. The first priest was not well received but when his replacement Aidan arrived from Iona, his gentle approach endeared him to the Northumbrians. Oswald granted him the island of Lindisfarne to build his monastery, which flourished, particularly in the latter years of the 7th century and throughout the 8th century, which saw the production of the Lindisfarne Gospels.

Oswald is noted for his piety and charitable deeds in life, and Venerable Bede recounts several acts of kindness that particularly stood out. Among them is the tale of the blessing of his arm by Aidan after Oswald broke up silver platters from his feast to be distributed to the poor at his door.

After eight years of rule, in which he was the most powerful ruler in Britain, Oswald was killed in the Battle of Maserfield while fighting the forces of Penda of Mercia, who then himself was defeated by Oswald’s brother Oswiu. Before he was killed Oswald knelt and prayed. Bede records, “…his life closed in prayer; for when he saw the enemy forces surrounding him and knew that his end was near, he prayed for the souls of his soldiers. ‘God have mercy on their souls,’ said Oswald as he fell.” Oswald’s last words have also been interpreted as asking for forgiveness of his murderers, an ultimate expression of the Christian ideal of turning the other cheek.

|  |

| St. Aidan Sculpture, Lindisfarne | Oswald and Penda in Battle at Maserfield near Oswestry, 5th August, 642. From the Queen Mary Psalter |

Following their deaths, Oswald and Aidan were revered as saints. St. Oswald’s relics were venerated, and a cult formed in England and on the Continent which thrived in the Middle Ages.

Venerable Bede’s use of St. Oswald as a Christian martyr gives us an insight into the world of the Anglo-Saxons. At this time, books were incredibly valuable and rare, so for the new Christian movement to flourish preaching and oral storytelling were vital. The Christians had to demonstrate the advantages and power of their religion, and stories that demonstrated the efficacy of their faith and which legitimized it in terms of the endorsement of the ruling classes were important in strengthening the faith of new converts and encouraging non-Christians to accept the faith.

Now that we better understand the historical importance of Bamburgh Castle, let’s find out about its excavation.

Bamburgh Research Project

Bamburgh Castle and its environs form one of the most important archaeological sites in Britain. The Castle contains layers representing more than two thousand years of continuous occupation, while the landscape around the castle is textured by over six thousand years of human history. The Bamburgh Research Project (BRP) is an independent, non-profit archaeological project investigating Bamburgh Castle and the area surrounding it. Individuals working for and with the Project are continuously unearthing treasures that not only enrich the writing of Venerable Bede but also provide clues to the community before the Anglo Saxon kings. Since 1996, archaeologist Graeme Young and his team have excavated inside and around Bamburgh in an effort to understand the site’s 2,000-year history and add to the legacy of Dr. Brian Hope-Taylor.

The discovery of the Bamburg Sword (see below) provides evidence that Bamburgh was indeed the home of kings as the technology involved in the making of the Bamburgh Sword would have made it a vastly superior weapon at the time of its making; one fit for a king. The only one of its kind ever found, it is on display in the Archaeology Museum at Bamburgh Castle.

| Discovered in 1960 by Dr. Brian Hope-Taylor, the Bamburgh Sword then disappeared until his death, when it was recovered from his apartment by the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historic Monuments of Scotland. About 80cm long, it is dated to the seventh century and is a rare example of complex pattern-welded swords: x-rays have revealed its blade is made up of six individual strands of carbonized iron bonded together to form the blade. Pattern-welded swords made up of four strands are more common and examples of this type were recovered from the Sutton Hoo burial. [Photo and Text from Bamburgh Castle: Digging the Home of Northumbria’s Kings] |

In Bede’s history, Bamburgh was accorded the dual status of “urbs” and “civitas, terms that indicate an extensive site of foremost importance. Further indication of this high status can be gleaned from the finds that have already become known from the excavations within the castle. These include small gold objects such as the famous Bamburgh Beast, strap ends, and fragments of a carved stone seat or even throne, recovered from beneath foliage within the grounds. All of these finds are currently on display in the castle’s archaeology museum. The recovery of such material supports the written evidence for the high status of the site during this period. [Bamburgh Castle: Digging the Home of Northumbria’s Kings]

A small, decorated gold plaque showing the Bamburg Beast.

Excavation includes St Oswald’s Gate and the outworks that lie beyond it. The gate and outworks connect Bamburgh the fortress to Bamburgh Village, and to the wider landscape and seascape beyond. The low-lying natural cleft in the bedrock was the entrance to the site from prehistory and has some of the least altered medieval structures available to be investigated today. The archaeological work below has been undertaken intermittently over a number of years and includes the fortress defenses, the routes that would have led to the village and farmland beyond and even includes a now lost port! Excavation also includes exploring a medieval tower with a well within its basement room.

The “Wing Wall” showing the narrow archway of St Oswald’s Gate. | In the northern part of Bamburgh Castle, a recent discovery has been found through archaeological excavations. Two buildings were unearthed and are believed to be fortified gatehouses. The gatehouse would have been the original entrance to Bamburgh Castle, protected by a barbican and a drawbridge. St Oswald’s Gate, as it is now known, would have provided safe access to a natural harbor on the coastline. |

Oswald’s Gate

Archaeologists knew from documentary evidence (monastic annals dated to 774 AD collated by Simeon of Durham in the 12th century) that the passage of steps leading to St. Oswald’s Gate was the early entrance to the castle. They investigated the area by lifting some of the late 18th century flagstones, leading to the gate, to reveal at least two phases of earlier surfaces, beneath which the bedrock was worn smooth, indicating an entrance in use for many generations. Bamburgh Castle: West Ward – Bamburgh Research Project]

Excavated post-holes shown in the foreground and a small section of the rubble wall foundation still in place at the top of image. | Within the Oswald’s Gate surviving evidence reveals well-constructed timber defenses that begin as deep-set post-holes, cut into bedrock, which are later replaced by a rubble foundation in a trench that archaeologists believe carried a large baulk of timber into which vertical planks would have been set to form a wall. It is easy to imagine the site as a kind of Iron Age fort like those we see on hilltops throughout the north. We know from Bede’s history that Bamburgh was a well defended timber fortress in the middle 7th century when Bede describes how Penda King of the Mercians (a large rival kingdom to Northumbria in the English midlands) demolished all the timber buildings. |

Among the goals of the Bamburgh Research Project team is to find artifacts that confirm the writings of Venerable Bede about Northumbria’s Golden Age. From the Bamburgh Project website, we learn that the Bowl Hole Graveyard was first discovered in the winter of 1816/17, following a violent storm that blew away a large volume of dune sand to reveal an ancient land surface and a number of graves marked out by stones set on edge. Although it was subject to limited antiquarian investigation in the 1890s and 1930s, few records survived, and the precise location of the site was not recorded.

Current research was intended to re-locate the site and undertake a limited excavation to provide information on the time period during which it was in use and its current state of preservation. During the course of the dig ninety-one individual skeletons were excavated and subject to scientific analysis by the University of Durham in a collaborative project with BRP, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC).

A combination of radiocarbon dates and the form of the burials, with very few grave goods, has led to the current interpretation that the cemetery was principally in use in the 7th and 8th centuries AD and that its inhabitants are likely to represent some of the earliest Christians in the ancient Kingdom of Northumbria.

Whilst it is often difficult to identify the cause of death, study of skeletal remains can reveal a great deal about the life of the individual. The people buried at the Bowl Hole had terrible teeth, with cavities and plaque very prevalent. Abscesses were all too common as well, even in young people in their twenties. Researchers surmise that this is a consequence of rich food. Other characteristics also stood out amongst this group, they were often tall and robust individuals, certainly much more so than the average for early medieval populations.

The scientific analysis of teeth also indicated that few individuals buried in the Bowl Hole Graveyard grew up in the immediate area of the castle. Many were from the wider British Isles with Western Scotland and Ireland well represented, due to the close early connection of the Northumbrian church with Iona. In a number of cases researchers traced people’s origins from beyond the British Isles, which means that they travelled an exceptionally long way to end their days at Bamburgh, from as far away as Scandinavia or even as far as the Mediterranean. Bamburgh was a well-known place even 1300 years ago.

Remains excavated from the Bowl Hole graveyard. | The Bowl Hole is an early medieval cemetery site just 300m to the south of Bamburgh Castle. It is thought to be the burial ground for the royal court of the Northumbrian palace that lies beneath the present castle. The excavation of the site was undertaken by the Bamburgh Research Project (BRP) between 1998 and 2007. The results of the excavation are now featured in a local exhibition ‘Bamburgh Bones.’ Photo and text from Anglo-Saxon life at Bamburgh Castle – Bamburgh Bones |

The Bamburgh Research Project is nearing the end of its excavation phase, and now publication will soon be the focus of most of the team’s efforts. The treasures found as a result of the project’s excavations and research support the writings of Venerable Bede. Bamburgh Castle was once home to the ancient kings of Northumbria and became a strategic and important capital for the kingdom. It saw the spread of Christianity and provided a home to the saint king, Oswald.