Medieval Christmas

Madonna and Child, Book of Kells

Link Between Pagan Yule and Christmas Festivities

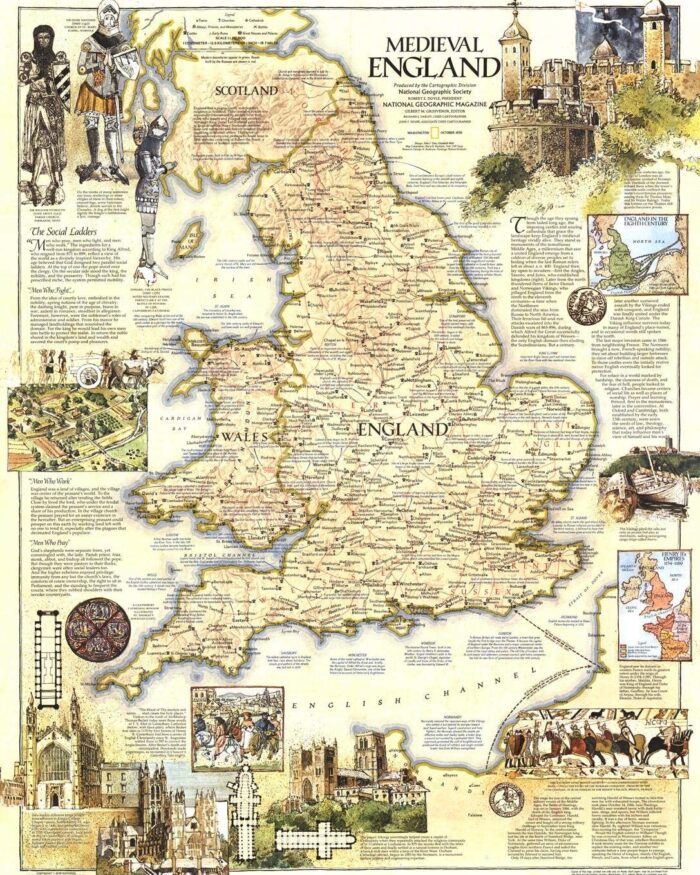

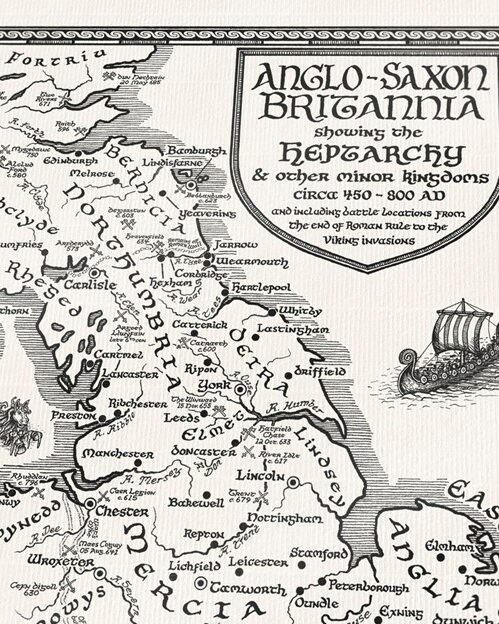

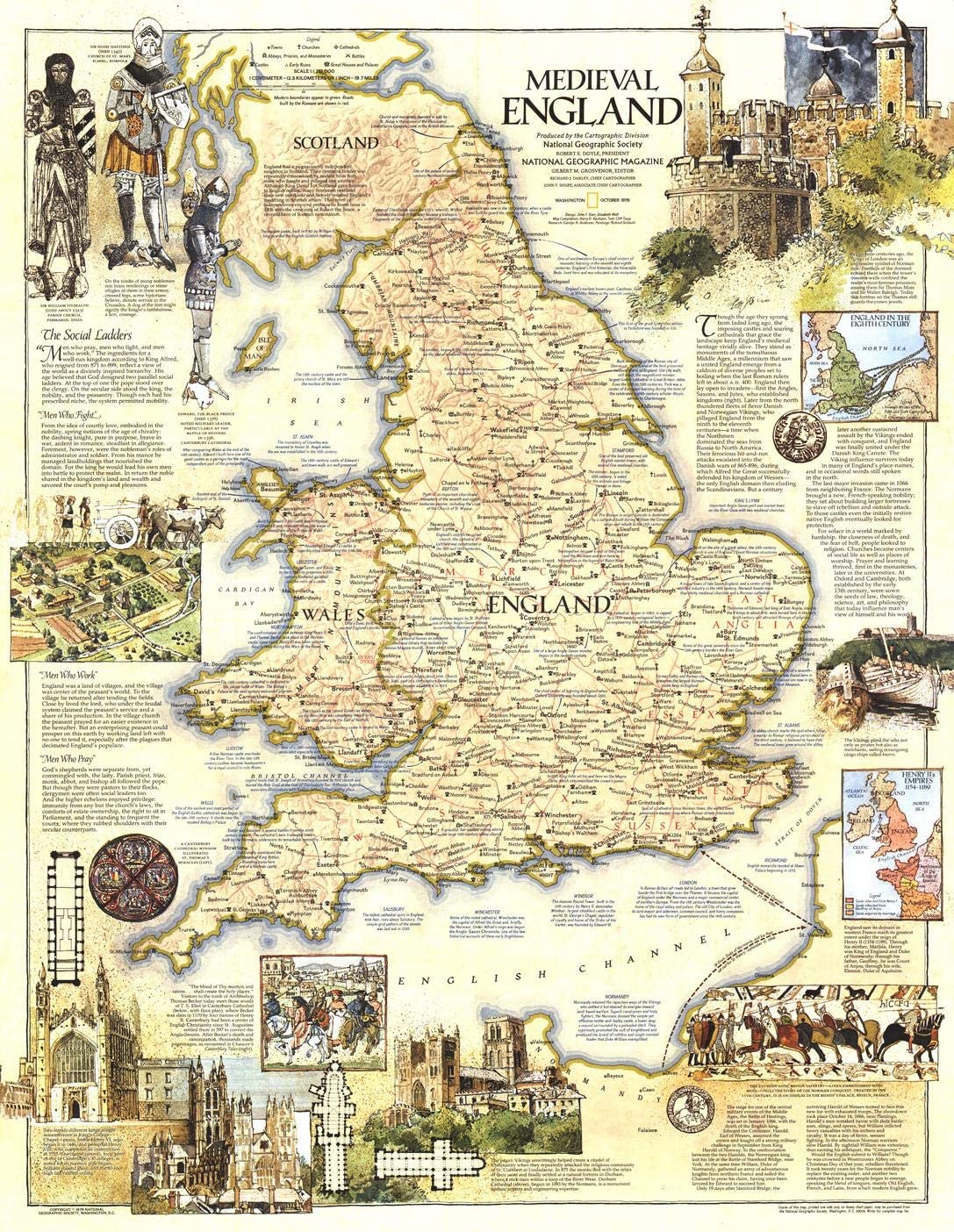

The original Germanic invaders – Angles, Saxons, and Jutes – were not Christian, but were still engaged in celebrations on the 25th of December.

Venerable Bebe | The Venerable Bede wrote in the eighth century that in the pagan tradition, this time of year was called Yule and had some association with fertility. The link between Yule and Christmas, where pagans celebrated birth and Christians celebrated Jesus’s birth from Mary, a mortal woman, is understandable. When the early Roman Church mandated in 380 the conversion of pagans, they also determined a policy of continuity to ease the change from one religion to another. Deciding on 25th December as the date of Christ’s birth was probably an intentional ploy by the Roman Church to recognize the previous pagan Yule celebrations. |

In the pagan festival of Yule, druids blessed and burned a log and kept it burning for twelve days as part of the winter solstice. The church introduced its own version of this–Candlemas, or the Feast of the Purification of the Virgin held on 2nd February. Medieval parishioners came to church with a penny and a candle to be blessed. Other candles were taken away to comfort the sick and dying or to give hope during thunderstorms. The Yule log gave the pagans a symbolic light to guide them through the harsh winter, while the Candlemas candle provided Christians with a similar source of hope and light during the chilly winter months.

The pagan festival of Yule morphed into the twelve days of Christmas; a series of religious feast days celebrated as part of the Roman Catholic religion. The joining of these two traditions meant ordinary people could celebrate the birth of Christ and their own salvation, as well as enjoy themselves with the feasting and fun associated with pagan tradition. Starting on Christmas Day, there were 12 days of religious celebrations, feasting, and entertainment that lasted all the way up to January 5th.

| One example of the heady mix of Christian and pagan is the tradition of the Lord of Misrule. This was someone appointed at Christmas to be in charge of Christmas revelries, which often included drunkenness and wild parties in the tradition of Yule. Again, the church had an equivalent, called a boy bishop. This tradition seems to come from ancient Rome, from the feast of Saturnalia. During this time, the ordinary rules of life were turned upside down. Masters served their slaves, and offices of state were held by peasants. The Lord of Misrule presided over all of this and had the power to command anyone to do anything. |  |

The Promotion of Christmas

Alfred the Great (King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899) was greatly influenced by the Frankish Court–his stepmother, Judith, was great-granddaughter of Charlemagne–and seems to have shared their view of the importance of Christmas as a festival. In one of Alfred’s laws, a holiday from Christmas Day to Twelfth Night was to be taken by all but those engaged in the most important of occupations. Everyone, even poorer people, stopped working for 12 days starting on Christmas Day. On Christmas Eve, people decorated their homes with whatever greenery they could find growing, including holly, ivy, mistletoe, and other evergreens. The green plants, still growing even in winter when other plants had died, were thought to symbolize eternal life. It was considered good luck to bring them into the home on Christmas Eve, but bad luck to do it any earlier. Because people were not meant to work over Christmas, women would decorate household items like spinning wheels, so that they would be unable to use them until after the 12 days.

Alfred the Great |  Kissing bough on display at Fairfax House in York |

Contrary to widespread belief, Christmas trees were around much earlier than the Victorian era, their roots being firmly in the Middle Ages. Indeed, the fir tree has medieval connections with Christianity in a legend involving a Northumbrian monk called Saint Wilfrid from the seventh century. Taking exception to the Druidic practice of worshiping oak trees, Wilfrid cut down a particularly venerated oak while surrounded by a group of his converts, but in the place of the cut tree, a fir sprouted. Wilfrid dedicated the new growth to Christ and thus the evergreen fir became part of Christian tradition. The custom of bringing a tree into the house was still many centuries in the future, but a nearby fir tree would often have been decorated al fresco with fruit, wafers, or candles to commemorate St Wilfrid’s dedication.

In eight hundred, the great Frankish king Charlemagne was crowned Holy Roman Emperor on Christmas Day at St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome. There were established Christmas traditions by this time, which were continued through the Anglo-Saxon period. The fullest account of Anglo-Saxon Christmas is given by Egbert of York (d. 766), a contemporary of Bede. In his account he states that ‘the English people have been accustomed to practise fasts, vigils, prayers, and the giving of alms both to monasteries and to the common people, for the full twelve days before Christmas.’

Perhaps most interesting in this early iteration of the Christmas period is Egbert’s mention of almsgiving, in which we can see the predecessor of modern Christmas presents. Alms were charitable relief given to the poor, without expectation of payment. We may link our present-day gift giving and the traditional festive fundraising of organizations such as the Salvation Army to Egbert’s discussion of charitable acts at Christmas.

Almsgiving: Image Taken from Facebook

Christmas Day

Christmas Day began with Midnight Mass. Church bells rang; candles were lit and at last the celebrations could begin!

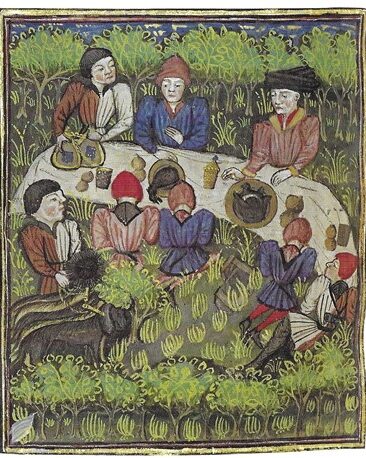

If you were lucky enough to be present at a noble Christmas banquet, you would have your fill of sumptuous starters and tasty treats. Medieval noblemen often had a boar’s head as their main dish, served with rosemary and an apple or an orange in its mouth. In the countryside it was traditional to kill a wild boar, cutting off its head and offering it to the goddess of farming to ensure a good crop in the coming year. But if boar was elusive, you might have goose or venison. You might even be served with swans, smothered in butter and saffron–with the King’s permission, that is. (They are still royal property today.)

Roast Swan: Museum of London

Contrary to what you might expect from how ‘brawn’ is understood today, in medieval England it was one of the most favored cuts of meat. It was usually a rich and dark cut, quite fatty, from boar or sometimes poultry. In order to prepare the dish, the fresh meat was deboned, bound with string, and then boiled until incredibly soft. It was then drained, cooled, and preserved in ale, cider, wine, or vinegar. Once ready for serving, it was presented in thick slices to be dispensed at the table.

England’s King John held a Christmas feast in 1213, and royal administrative records show that he ordered copious amounts of food. One order included twenty-four hogsheads of wine, two hundred heads of pork, 1,000 hens, 500 lbs. of wax, 50 lbs. of pepper, 2 lbs. of saffron, 100 lbs. of almonds, along with other spices, napkins, and linen. If that was not enough, the King also sent an order to the Sheriff of Canterbury to supply 10,000 salt eels.

Even at a slightly lower level of wealth the Christmas meal was still elaborate. Richard of Swinfield, Bishop of Hereford, invited forty-one guests to his Christmas feast in 1289. Over the three meals that were held that day, the guests ate two carcasses and three-quarters of beef, two calves, four does, four pigs, sixty fowls, eight partridges, and two geese, as well as bread and cheese. No one kept track of how much beer was drunk, but the guests managed to consume forty gallons of red wine and another four gallons of white.

Christmas Pie by William Henry Hunt (1790-1864) | For poorer people, meat was a luxury that they often could not afford, but at Christmas, they would have goose as a festive treat. Though not allowed to eat the best parts of the deer, a nobleman full of Christmas spirit might allow his poor tenants to have the leftovers. Known as ‘umbles,’ these parts were usually the heart, liver, tongue, feet, ears, and brains. They were made into a pie. It’s easy to see where our modern expression about having to ‘eat humble pie’ comes from. However, if you were not into deer entrails, the church generously offered a fixed Christmas price of seven pence for a ready cooked goose–although that was about a day’s wages. |

Mince pies were also eaten at medieval tables. Featuring cinnamon, cloves, and nutmeg in token of the gifts of the three Magi, mince pies were originally larger and shaped into ovals to represent the manger. Often a pastry was made that was shaped in the form of the infant Jesus and was placed on top of the pie. The mince pie would then be eaten in celebration of the birth of Christ. If you made a wish with your first bite people said it would come true. But do not refuse if someone offers you a pie, or you might suffer bad luck.

In Great Britain especially, but also in other English-speaking countries throughout the world, it’s hard for many people to imagine Christmas without mince pie.

Mince Pies

| To wash down all the rich food there were two fine festive tipples. Lambswool was a hot concoction of mulled beer with apples bobbing on the surface. There was also Church Ale, a strong brew reserved only for Christmas and sold in the churchyard or even in the church itself. |

The proximity of alcohol to the church coincides with one or two of the livelier Christmas traditions. Carols, such a staple part of today’s Christmas diet, were prohibited in many European churches because they were considered lewd. They were often accompanied by dancing. The leader of the carol dance sang a verse of the carol, and a ring of dancers responded with the chorus. However, carol dances were suggestive of the fertility traditions of pagan song and dance cycles and were thus considered too coarse for church. A famous Christmas song of today is The Twelve Days of Christmas, where a list of presents given to the singer by their ‘true love’ is recounted. The gifts range from ‘eleven lords a-leaping’ to ‘a partridge in a pear tree.’ In medieval times this was a game set to music. One person sang a stanza, then another would add his own lines to the song after repeating the first person’s verse.

Oliver Cromwell and his Puritan government tried to ban the frivolities of Christmas and some of the more vernacular traditions which developed during medieval times. But he did not succeed for long. Many of our modern traditions come from the early mingling of the Christian and the pagan worlds. Whilst the church secured Christmas as a truly religious Christian holiday, peasants quietly continued with the old ways. The result is the rich and eclectic mixture of old and new that characterizes Christmas today. What better way to encapsulate the spirit of Christmas than this fusion of various times, religions, and peoples to make a festival that has earned its place as one of the favorites in our calendar.

Sources:

King Alfred and a Saxon Christmas at Wareham

Anglo-Saxon Christmas

Reading Museum

The Twelve Days of Christmas

Time Travel: Britain.com

Medievalists.net

Medieval Wanderings