The Romans Leave Britain

It wasn’t called Britain in 400, but let’s use that name for simplicity’s sake. At that time, Romans ruled in the south and Picts and the Scotti in the north.

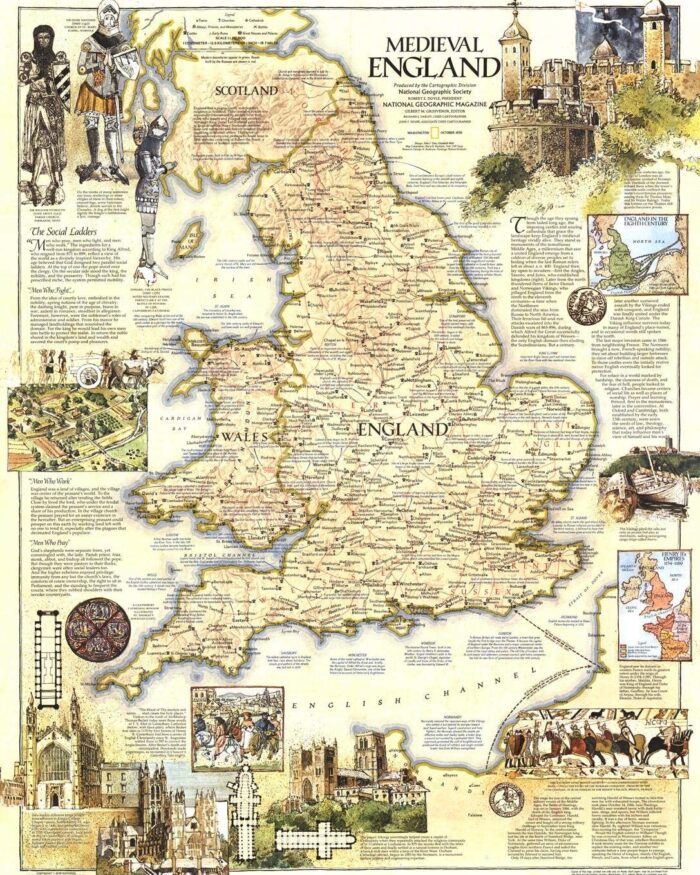

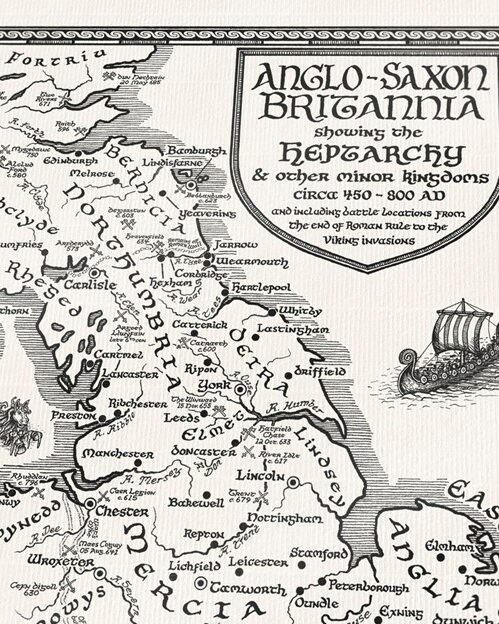

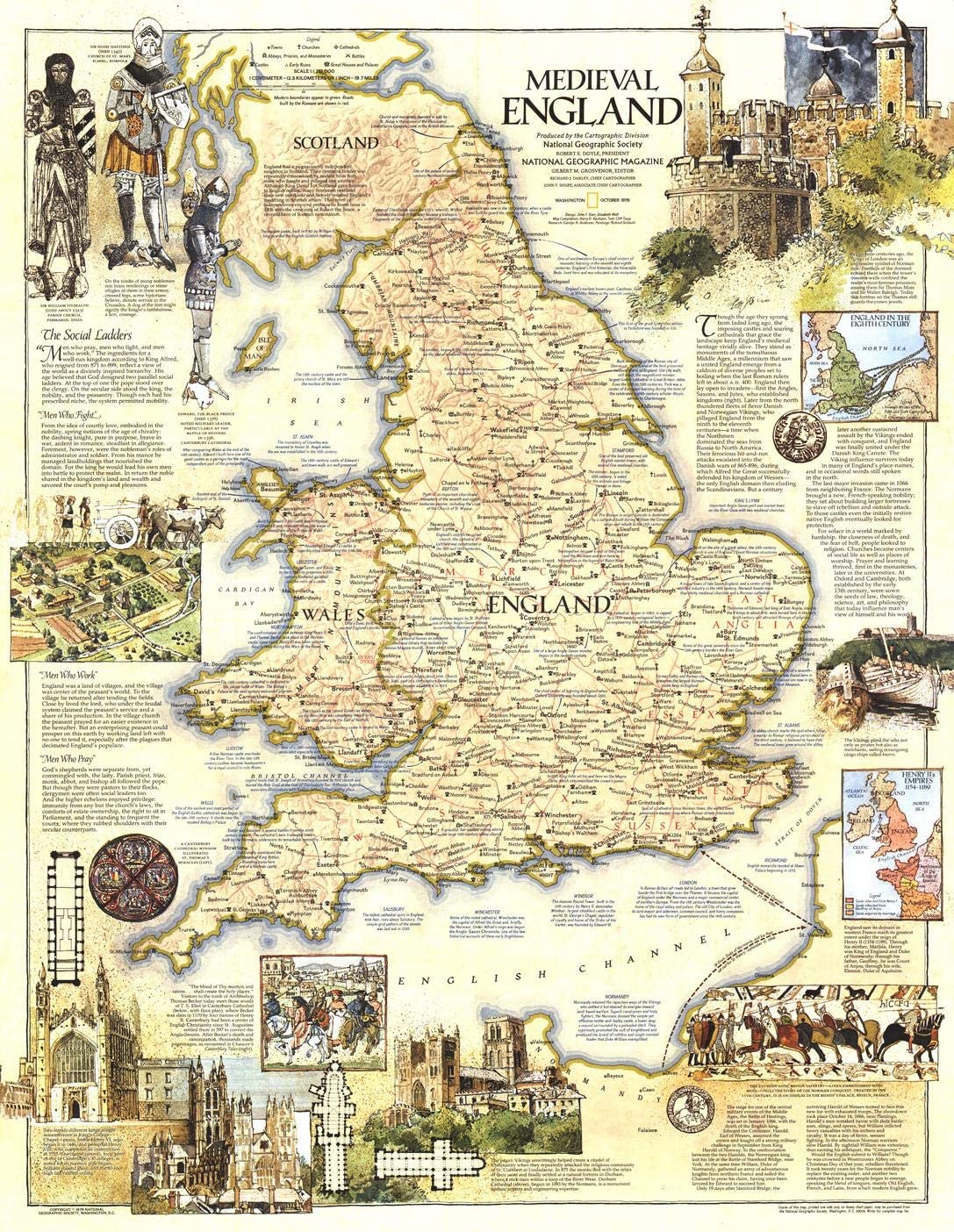

| At left is a very simplified map of Britain in 400. For a more detailed map showing British territories and kingdoms established in the fourth and fifth centuries, check out Map of the Island of Britain AD 450-600. In 400, Britain was a diverse and dynamic region. It was still part of the Roman Empire, though Roman control was weakening. The population included: * Romans: Roman officials, soldiers, and settlers who had been in Britain since the Roman conquest in 43 AD. * Britons: The native Celtic people who had lived in the region for centuries. They were a mix of tribes with their own local leaders and cultures. * Picts and Scots: Tribes from what is now Scotland and Ireland, respectively, who frequently raided Roman Britain. * Germanic Tribes: Early settlers from Germanic tribes, such as the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, who began arriving in larger numbers after the Roman withdrawal. |

The well-known date of Britain’s final official break from Rome is AD 410, but by that time Roman military support was sporadic and seeing their opportunity, various groups began raiding and settling on the island.

Scholars refer to the individuals living in the southern part of Britain before and during the Roman occupation as Celtic Britons. Celtic Britons, especially those along the east coast, had adopted the Roman way of life. Heavy Roman military presence was found here and inhabitants lived in Roman-style houses within Roman settlements. They spoke a type of British Latin (Celtic and Gaelic), wore Roman-style cloths, and used roads like those found in the rest of the Roman Empire. It is interesting to note that Celtic Britons were not native inhabitants of the island either. They, too, had immigrated from other areas.

The Scotti of Ireland and the Picts from Scotland had been regularly crossing over into Roman territory in Britain. However, some other groups who did not have a long history of attacking Britain (e.g., the Angles from what is now the border of Germany and Denmark (Schleswig Holstein), the Saxons from what is now northern Germany, and the Jutes from southern Denmark) began to invade the island in the first half of the 5th century. For convenience, historians typically refer to these new immigrants as Anglo Saxons.

A depiction of Angles, Saxons, and Jutes crossing the sea to Britain equipped with war gear from the Miscellany on the Life of St. Edmund.

John Speed’s map of c.1611 depicts the kings who reportedly conquered parts of southern Britain and founded the earliest Anglo-Saxon kingdoms there in the 5th and 6th centuries Here we see Hengist of Kent, Ælla of Sussex, and Cerdic of Wessex. IMAGE: Cambridge University Library

One reason scholars attribute to the new migration of Anglo-Saxons is climate change. Warmer English summers meant better crops; and Britain was far less likely to flood than Denmark, Holland, or Belgium. Also, Anglo-Saxon mercenaries had for many years fought in the Roman army in Britain and some had already decided to remain on the island instead of returning home. Roman soldiers also remained because when they had served for twenty-five years, they were bestowed with attractive land in Britain.

The transition from Roman rule to Anglo Saxon rule was not a smooth one. In time, the Anglo Saxons merged with the Celtic Britons. They moved into their villages, shared farmland, intermarried, and commanded military forces. Over time, some rose to power as leaders of villages, towns, and regions.

The Anglo Saxons organized themselves into social classes similar to those in their native countries. At the head of the tribe was the ‘chieftan’, a title that later transitioned to ‘king’. The position of chieftan (or king) passed through male bloodlines, with the ruler’s eldest son as the heir. The Anglo Saxons believed that the male bloodline had to become pure because it was the family’s link back to Woden, their god of war, wisdom, and poetry.

Medieval travelers in 410 traveled slowly over land that was rough and frequented by bandits. We would have probably traveled on foot to nearby villages, markets, and other destinations. For longer distances, and if we had a little wealth, we would ride horses or use carts to carry our possessions. Britain still had a network of Roman roads, which were crucial for travel and trade. However, in rural areas, we would rely on local paths and tracks, often little more than dirt trails. If we traveled along the coast or within a river, we would use boats for fishing and short range travel, and larger ones for trading and movement across the Channel and along the coast.

What we know of life in Britain around 400 has been pieced together from sketchy written sources and the chance survival of archaeological evidence. Over the last decades, however, the discipline of archaeology has experienced a spectacular growth and we have learned much about how people lived during early medieval times through DNA and population studies, isotope analysis, and y-chromosome evidence,

A hoard of Roman gold coins found below the floor of a Roman house in Corbridge, UK

Metal-detectorist discoveries recorded by the Portable Antiquities Scheme have Metal-detectorist discoveries have transformed the number of finds available to scholars. This early medieval find is a 5th- to early 6th-century cruciform brooch from Lincolnshire.

Historians often use the term “Dark Ages” to describe the time after Roman rule of Britain. This was not the case. The Anglo Saxons brought change, injecting a new set of religious beliefs, military tactics, and literature.