Vortigern: Myth and Legend

Who knows whether Vortigern really existed. Sources of information on what happened in Britain during the fifth century provide tales that have lived on through the ages but may be a little suspect in their authenticity. We highly recommend watching the YouTube video Can We Trust Bede and Gildas? before going any further. It will provide context for much of what we will be learning about early medieval Britain.

To summarize this video, the works by Gildas and Bede, and probably others documenting individuals living and events happening at this time, may be inaccurate for the following reasons:

- Sources of information about Britain in the fifth century were written by individuals who lived long after the events and people they describe.

- The authors of written sources did not necessarily live near the locations they describe and may have had little or no direct exposure to the culture of the inhabitants.

- Their work may be based solely on exaggerated hearsay from others.

- Gilda’s work came before Bede’s, and it is easy to see that Bede just copied whatever Gildas had written. This happened with other documents as well. It seems that, like the game Telephone, one author copied another and so on.

Accepting that these sources may be highly divergent from what truly happened, let’s take a look at the accounts that guide our impressions of life in Britain in the fifth century.

| Up first we have De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae (The Overthrow and Conquest of Britain also translated as The Ruin and Conquest of Britain), written by the monk Gildas in the sixth century some one hundred and fifty years from when events he recounts took place. There are many editions and translations, the closest to the original being a part of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica series. A copy is readily available. |

| In the eighth century, the monk, Venerable Bede put his own spin on the fifth century, authoring the Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People). A page from the Old English translation of Bede’s is shown here. Many different editions and translations of the manuscript survive, one of the earliest at Cambridge University Library. A copy is readily available. |

| The question of the nature of the text of the Historia Brittonum is one that has caused intense debate over the centuries. Some scholars have taken the position that treating the text as anonymously written would be the best approach as theories attributing authorship to Nennius have since been disputed by subsequent scholars. It is thought to be written around 828. Various revisions may be found in European and British libraries. A copy is readily available. |

| Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a chronological account of events in Anglo-Saxon and Norman England, first assembled in the reign of King Alfred (871–899) from materials that included some the Venerable Bede’s Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum, genealogies, regnal and episcopal lists, a few northern annals, and probably some sets of earlier West Saxon annals. The compiler also had access to a set of Frankish annals from the late ninth century. Various revisions and translations exist. There are seven original copies of the text that reside in the British Library and two other public libraries in the United Kingdom. A copy is readily available. |

| The History of the Kings of England, originally titled, De gestis Britonum (On the Deeds of the Britons) and later Historia Regum Britanniae was completed in 1136 by the Catholic cleric Geoffrey Monmouth. The History of the Kings of England traces the story of Britain from its supposed foundation by Brutus to the coming of the Saxons some two thousand years later. It portrays legendary and semi-legendary figures such as Lear, Cymbeline, Merlin the magician, and the most famous of all British heroes, King Arthur. It is as much myth as it is history, and its accuracy was questioned by other medieval writers. But Geoffrey of Monmouth’s powerful evocation of illustrious men and deeds captured the imagination of subsequent generations, and his influence can be traced through the works of great British writers. Over two hundred surviving manuscripts of this work exist as various revisions and translations including notable ones at the Bern Burgerbibliothek and Lambeth Palace. A copy is readily available. |

There is little archaeological evidence to support some accounts in these documents and it is hard to determine how much influence De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniaehad on sources that followed. While there is evidence that some leaders and events mentioned in these chronicles did exist, the stories about them may have been altered over time. Why spend so much space on these resources if they do not accurately reflect what actually happened in Early Medieval Britain? The answer is because these five sources are now part of Britain’s culture and are considered history, whether factual, myth or legend.

The accounts of the warlord Vortigern from the Anglo Saxon monks Gildas and Bede and Catholic cleric Monmouth remain perfect examples of historical fiction written about the Early Medieval Period. The story put forward is that when the Romans began pulling military support from Britain in the early fifth century, Vortigern took a leadership role in England and Wales. At this time, those in Europe were being invaded by armies from the East and the Romans formally ended military support in Britain in 410 to put all military efforts toward protecting their own land. This time period is regarded as pre-Anglo Saxon England.

| Vortigern had no army. He was under attack from the Scots who actually at the time were from what we now call Ireland; the Picts attacking from eastern and northeastern Scotland; the Angles, Saxons and Jutes coming from Germany; and the Danes attacking from the East. According to monks Gildas and Bede, Vortigern decided that since the Saxons were far from united and many were mercenaries, he would hire them to fight against invaders some of whom were Saxons as well. |

A Depiction of a Pict Warrior Painted as Described in Roman History | The Picts were so named by the Romans who observed and wrote about them, but as was the case with many ancient peoples, the Picts did not refer to themselves that way. “Pict” is believed to be a derivation of “The Painted,” or “Tattooed People,” which described the blue tattoos with which the Picts covered their bodies. |

It was the monk Venerable Bede, writing in the eighth century who gave Vortigern the title “High King of the British.” Understand that the word ‘king’ was not used in fifth century Britain, so no one then would have called him that! Bede also gave names to two Saxon leaders Hengist and Horsa although historians are not sure if they even existed! According to Bede, a group of Saxon mercenaries arrived in Britain between 446 and 454. Led by warlords Hengist and Horsa, they were welcomed by Vortigern who had hired them to fight off the invaders. They built forts along Britain’s eastern coast and successfully fought off raids, even those from their relatives. To pay them for their efforts, Vortigern gave the Saxon mercenaries land in Britain. Bear in mind that the collapse of the European economy was taking place at this time with the fall of the Roman Empire, so although Vortigern might have had lots of money, it may not have value. It would have been wise for the Saxons to demand land.

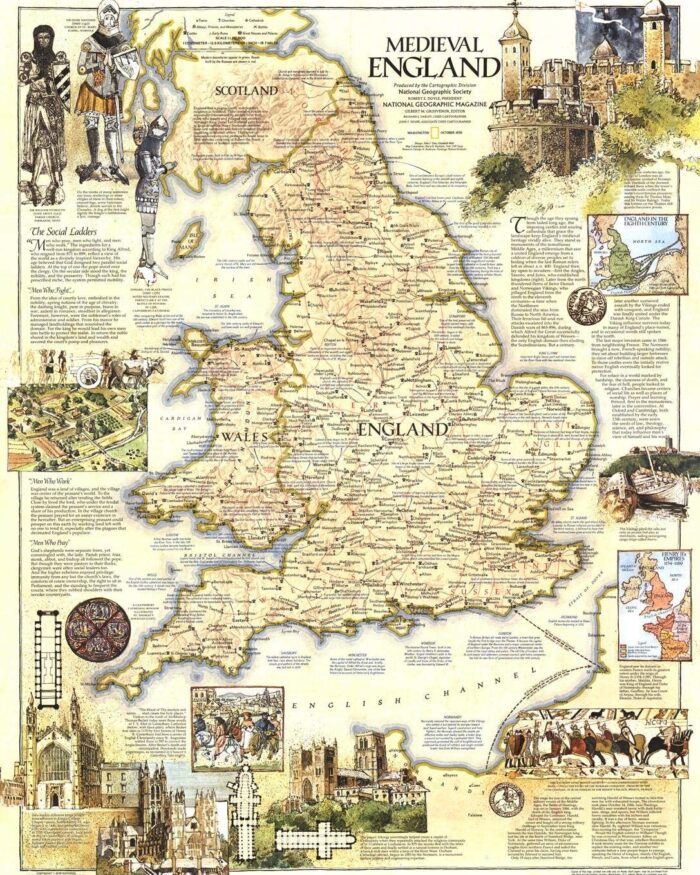

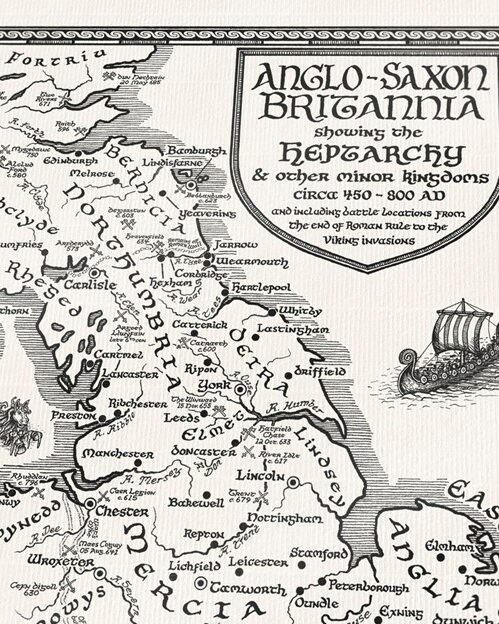

Vortigern gave the Saxons the territory we now know as Kent, eventually one of the seven kingdoms of the Heptarchy, which we will discuss a little later. Kent was a small kingdom on the southeast shore of Britain. It was Vortigern’s hope that, as more of Hengist and Horsa’s compatriots joined them, that Celtic Britons and Saxons could work together.

From the mid-fifth century, Anglo Saxon tribes began to migrate in large numbers into southern and eastern England. With trade severely disrupted, the old Roman administrative apparatus expiring, and civil war throughout the island, the hallmarks of Roman life – towns, villas, the Latin language, literacy, Christianity–fell into steep decline. These had all but vanished by five hundred.

The Anglo Saxon invasion broke up Britain into smaller parts called Kingdoms each ruled by a separate king or sub-king. These kingdoms were established during the late 5th century until the end of the Anglo Saxon era in the 9th century due to the Norman conquest.

According to accounts byGildas, Bede, Nennius, and Monmouth, many in Britain viewed both Vortigern and the influx of Saxons in a negative light. In the mid fifth century, ‘Make Britain Great Again,’ would have been a winning campaign slogan, apparently. Even though Gildas refers to Vortigern as ‘Supreme Lord,’ he is clearly not a fan. Nennius downright hates him, presenting him as weak-willed and foolish — a thoughtless king who cared more about his own pleasure and comfort than the welfare of the people and who engaged in “pagan acts” in defiance of Christian values and morals. He described the Saxons as “heathens” who set about destroying the country as soon as they had driven out the Picts and Scots and routinely designates to them animal imagery such as ferocious dogs or lions.

According to Monmouth, Vortigern fell in love with and married Hengist’s daughter, the Saxon Rowena, divorcing the daughter of the Roman Emperor and national hero, Magnus Maximus. After that interesting decision, his son Vortimer took up the battles to regain power from Hengist, Horsa, and the Saxons and Vortigern decided to retire. Much battling ensued and according to Monmouth, Vortigern headed west to what is now Wales to build a protective fortress in which to hide out. The fortress kept crumbling and in desperation he consulted with his magicians who told him that he must sacrifice a youth who had no father and sprinkle the blood on the foundation and then the tower would successfully rise.

And guess who that fatherless youth was?

Yes! Merlin! I’m not makin’ this up! Geoffrey is!

| Merlin depicted in the Nuremberg Chronicle, by Hartmann Schedel (1440-1514). This depiction of Merlin is part of the Chronicle’s rich collection of woodcut illustrations, which provide a visual representation of historical and legendary figures. |

Merlin is chosen as the sacrifice but, instead of submitting, he defies the king, saying, “Bid thy wizards come before me and I will convict them of having devised a lie” (VI, 19).

He also tells them he cannot be the sacrifice because he has other fish to fry with Arthur.

He also tells Vortigern that the earth under the fortress contains two dragons or serpents fighting, causing the ground to be unsteady. He tells Vortigern to excavate the site. Vortigern follows his advice, and the two dragons emerge – one red and one white –and begin battling furiously. As the red dragon drives out the white dragon, Merlin prophesies that this symbolized the British defeating the Saxons.

Not knowing when to cease and desist, Merlin goes on to prophesy Arthur’s dominance, and the course of English history for an indeterminate amount of time.

And that’s not all. He is also remembered for saying:

“The Hedgehog will hide its apples inside Winchester and will construct hidden passages under the earth.”

“In that time the stones shall speak.”

“In the days of the Fox a Snake shall be born and this will bring death to human beings. It will encircle London with its long tail and devour all those who pass by.”

“A man shall wrestle with a drunken Lion, and the gleam of gold will blind the eyes of onlookers.”

There are hundreds more but let us travel onward.

No one is sure how Vortigern died. In some sources, he is burned in the previously mentioned wooden fortress. In others, he loses his mind and roams the mountains.

What we do know for sure is that Merlin achieved fame and fortune in Hollywood, starring in Disney’s “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” and “Sword in the Stone,” “Transformers,” “Son of Dracula,” “Kids of the Round Table,” “A Kid in King Arthur’s Court,” “Shrek the Third,” and additional creative products such as his own mini-series and TV series.