Æthelberht of Wessex and the Vikings

Æthelberht, also spelled Æthelbert, Aethelberht, Aethelbert or Ethelbert, birth c. 835/crowned King of Wessex, 860 at age 25/death 865 at age 30/spouse, never married

House: Wessex/Father, Æthelwulf, King of Wessex/Mother, Osburh

Children: Two sons, Aldhelm, Æthelweard

Reign: 860 to 865

King Æthelberht of Wessex

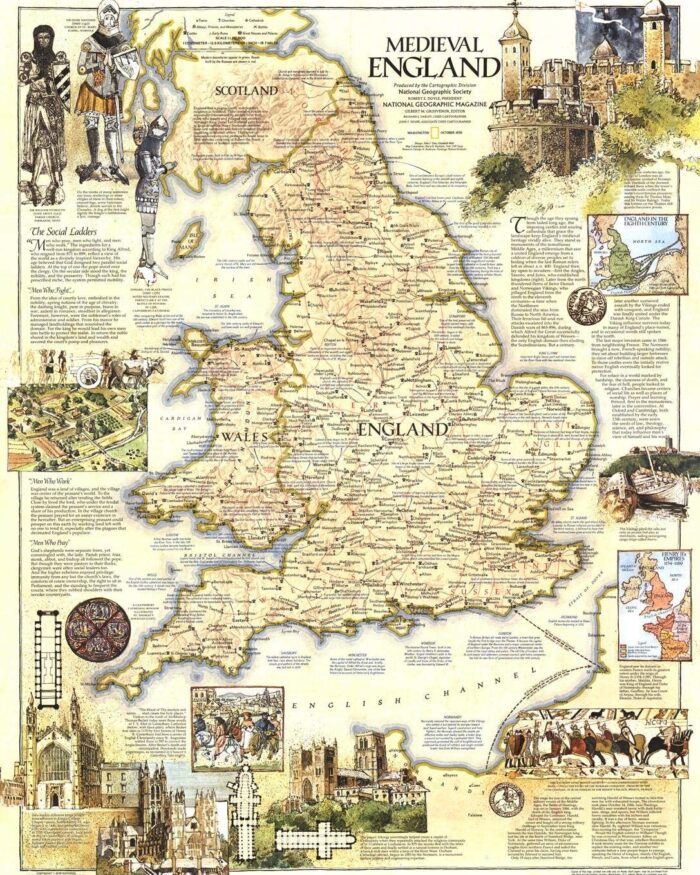

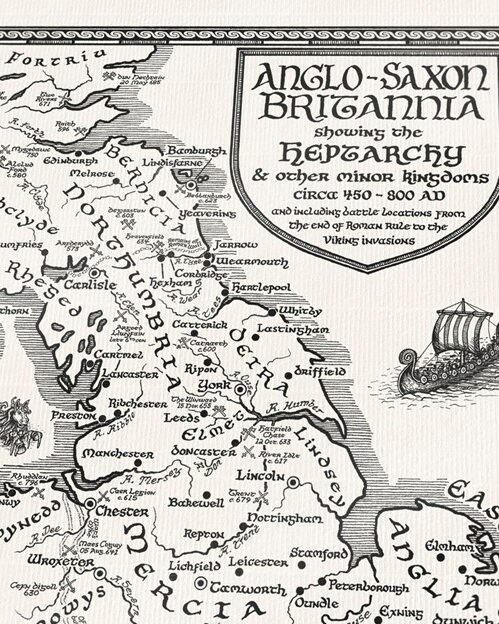

You are not seeing double; there were two kings in Medieval England named Æthelberht. We discussed Æthelberht (cc. 560-616) of Kent in Localized Leadership. Now we come to the second Æthelberht, King of Wessex who ruled over both Wessex and Kent for five years until his death. Few of Æthelberht’s deeds are recorded, but historians tell us that his reign was plagued by raiding Vikings. Viking raids were sporadic until the 840s but by the time Æthelberht became king, the Danes began to winter in England and assemble larger armies with the intent of not just marauding but of conquest.

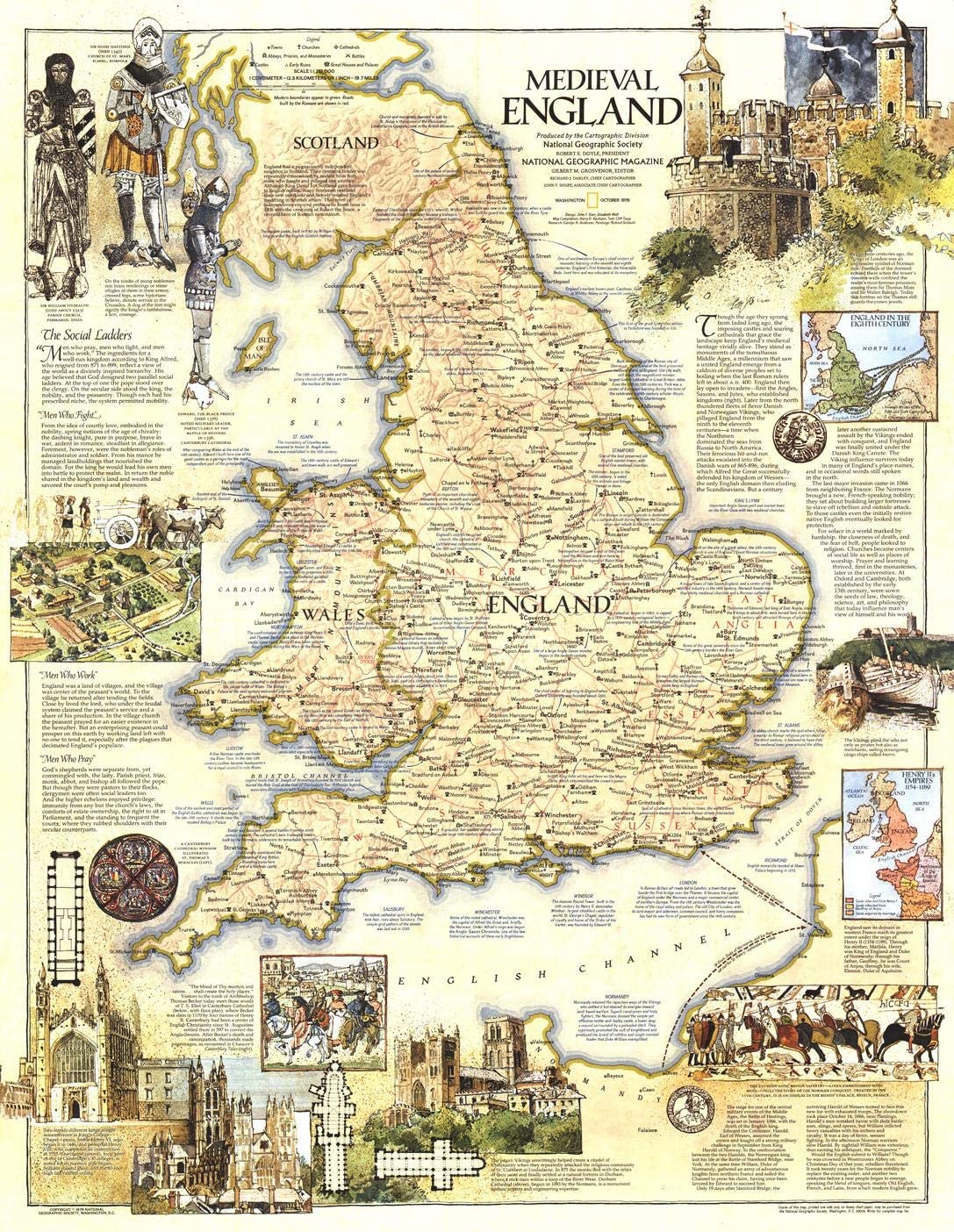

Vikings traveled from Scandinavia to Britain during Æthelberht’s reign. They mostly settled in the Danelaw, to the north and east of England.

Some Norwegian Vikings or ‘Norse’ sailed to Ireland. Some Swedish Vikings made settlements in Scotland, and on the Shetland and Orkney Islands. Vikings also settled on the Isle of Man and often raided Wales, but few made homes there.

There were several reasons why Viking attacks increased during the ninth century. Prior to the attack at Lindisfarne, there was plenty of contact among those living in Britain, Francia and Scandinavia. Trade networks extending across the North Sea and into the Baltic were developed and flourished. However, although kings and monasteries were growing rich on trade profits, little of this wealth found its way to those who were actually doing the hard work of trapping and trading the skins that sold in London or Aachen.

The Scandinavians knew all about the rich coastal communities of the kingdoms to the south and they also knew that they were not well defended. It is believed that the Viking Age began in Britain when Scandinavian boat-builders added sails to their ships which allowed them to travel directly across the North Sea to Britain. This took Britain by surprise as, according to York scholar Alcuin “Such a voyage was not thought possible” (see The Vikings: Culture and Conquest by Martin Arnold)

Viking Longship Replica

Emma Groeneveld (CC BY)

Source: World History Encyclopedia: Viking Ships

Events in what was then Francia also led to increased Viking raids on the British coasts. In 814, Charlemagne died and upon his death the once prosperous realm dissolved as his descendants fought each other for power. Because he had not appointed rule of his realm to one son upon his death, the Franks had to split the realm into three parts for each of his sons. On the one side lay east Francia (which would go on to become Germany), in the middle was Lotharingia and on the other side lay west Frankia (which would go on to become France). The Vikings capitalized on the fact that divided in three, the area once consolidated under Charlemagne now lacked the centralized power and strong military of the past. Parties of Vikings gained wealth from sacking such cities as Orleans, Tours, Noyon, Amiens, Chartres and Paris. They gained huge amounts of money by seizing hostages for ransom, or demanding compensation for not raiding an area. When the king of west Francia, Charles the Bald, began building fortifications on the Seine that made raids more difficult, Vikings began to turn their attention to Britain.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle coined the name “Great Heathen Army” to describe the Viking military force which arrived in Britain during Æthelberht’s reign. Led by three of the legendary Ragnar Lodbrok’s five sons—Halfdan Ragnarsson, Ivar the Boneless, and Ubba—the army embarked on a 14-year campaign of invasion and conquest against the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. While historical sources provide no definitive figures on the army’s size, it was widely regarded as one of its time’s largest and most formidable forces. [The Great Heathen Army: A Viking Invasion of England]

Source: The Great Heathen Army: A Viking Invasion of England

Despite continuing Viking raids, King Æthelberht ruled ‘in good harmony and in good peace’ according to the Anglo Saxon Chronicle. He reunited the kingdom, merging Sussex, Essex, Kent and Wessex. Unlike his predecessors, he did not put a family member on the throne of Kent as a subking, but rather ruled the kingdoms himself. This meant that virtually all of southern England was one unified kingdom. Æthelberht seems to have gathered together an assembly of both West Saxon and Kentish representatives to witness his charters, another sign of how he pulled together the disparate parts of southern England into one body.

Æthelberht died of unknown causes in the autumn of 865. He was buried at Sherborne Abbey in Dorset beside his brother Æthelbald but the tombs had been lost by the sixteenth century. He had no known children and was succeeded by his brother Æthelred.

For more information on Viking events in Britain check out Martin Arnold’s “short history.”