Localized Leadership

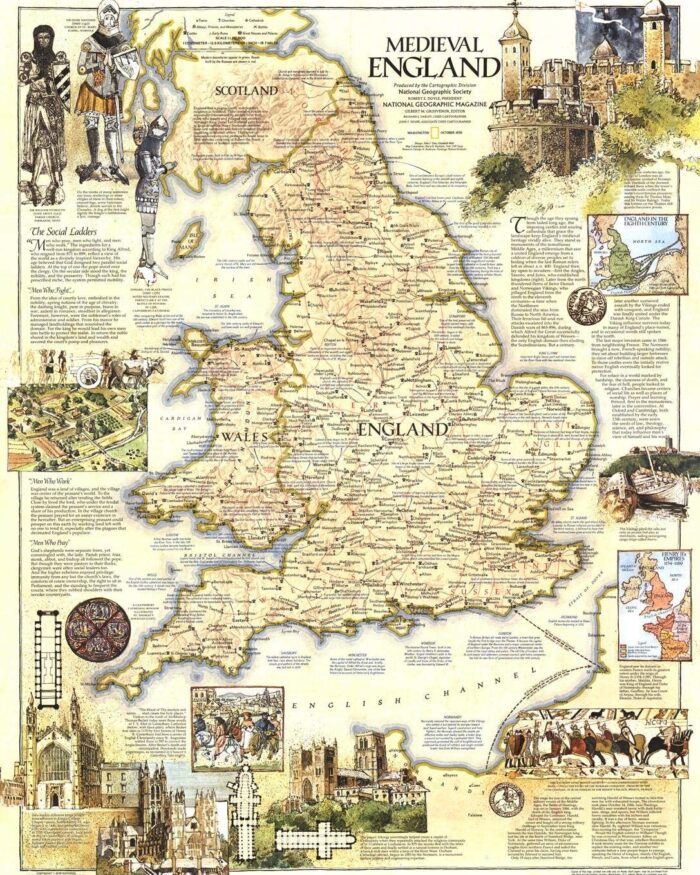

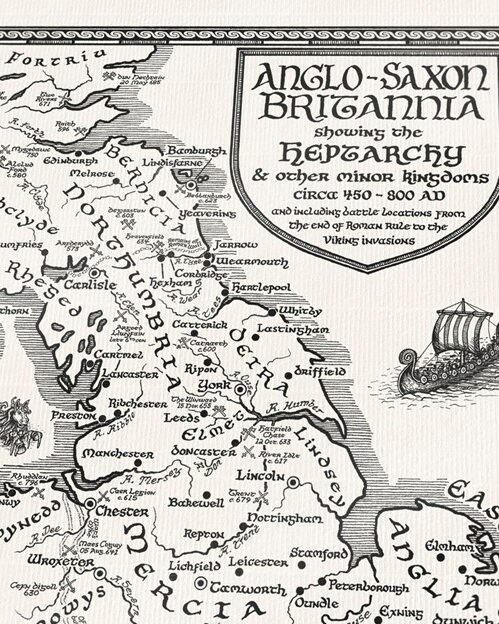

After the Romans no longer governed or financially supported Britannia, a patchwork of small kingdom or states cropped up, some governed by Celtic Romans who made Britannia their home; some governed by Celtic Britons, who had inhabited the island pre-Roman occupation; some governed by the Irish coming from the west, and some governed by the Angles and Saxons coming from the east.

To the north of Wales in modern day Scotland were small states like Strathclyde (sixth century) more influenced by the Irish and Celts than the Romans. One of the early rulers of Strathclyde was Tutgual, a Celtic Briton warrior king who protected his subjects from invasions. Legend has it that Tutgual’s whetstone, listed as one of the ‘Thirteen Treasures of Britain’, “would sharpen the weapon of a brave man so that a wound from his blade would be certain to be fatal; whilst it would not only blunt the weapon of a coward, but render it incapable of harming anyone.” [Tutgual Tutclyd, King of Strathclyde]

Source: Strathclyde

Heptarchy AD 650 | Among the early Angle leaders, several stand out because of their influence on English culture in future years. One such leader was Penda (c. 625-655), a leader in Mercia who constantly vied for dominance with Northumbrian kings. In 655 AD at the Battle of Winaed, Penda was defeated which was a turning point in history because he was the last of the Anglo-Saxon ‘kings’ to have rejected Christianity over Paganism. His defeat effectively marked the demise of Anglo-Saxon Paganism, something that would never be restored. |

Stained glass depiction of the death of Penda of Mercia, Worcester Cathedral, England

Photo by violetriga. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Æthelberht (cc. 560-616/618) of Kent represents another Angle leader, one of the first to look beyond his rather small kingdom for support and power. He married Bertha, the daughter of the Frankish king Charibert I, securing an alliance with a powerful state of Europe at that time. He was the first king to convert to Christianity and it was during his leadership that Pope Gregory the Great sent Augustine and his missionaries to build a church in Canterbury and choose it to be the seat of the first archbishop in 603. Under St Augustine’s guidance and Æthelberht’s instruction, churches were established throughout the land and the people began to gradually convert to Christianity.

Settlements of Angles, Saxons and Jutes in Britain, c. AD 600

Penda of Mercia was the last Mercian king to die a non-Christian, while most Anglo-Saxon kings converted to Christianity. The image shows Æthelberht, who was King of Kent from 589 to 616 AD, being baptized by St Augustine of Canterbury. (Public domain) Source: Ancient Origins

St Martin’s Church, Canterbury was the private chapel of Queen Bertha of Kent (died in or after 601). In the early 8th century Bede wrote in his History that it was here that Queen Bertha went to pray. There are several walls that date from at least her time.

The church sits on the hill overlooking St Augustine’s Abbey. This is quite appropriate as together they form the Canterbury World Heritage Site (UNESCO) recording the coming of Christianity to England in 597.

This is the oldest church in England that has been used continuously as a church since at least the 6th century and possibly since the 4th century under the Romans, as there is much Roman material in its walls. The church is thought to have been a Roman mortuary chapel before 400, as the area has produced many Roman burial sites and the Roman road into Canterbury from the Roman port of Richborough passed close by. It was in this church that St Augustine baptized Æthelberht. Source: RuralHistoria

St Augustine’s Cross stands close to the site at which an important meeting between St Augustine and King Æthelberht of Kent is said to have taken place in 597.

Source: History of St. Augustine’s Cross