The Galloway Hoard

Anyone who has enjoyed the award-winning program Vikings (2013-2020) has undoubtedly wondered what happened to the objects buried for safekeeping throughout Scandinavia and across Great Britain and Ireland during ‘The Viking Age’ (793-1066). Theories concerning the purpose of Viking Age hoards include the belief that the buried sites substituted for banks. Individuals hid their wealth with the intention of later retrieval. Norse sagas contain examples of wealth buried in the ground to be accessed in the afterlife. Treasures might have been buried to seal an oath or to claim land. Many Viking Age hoards from Ireland have been discovered in or near churches. These finds have led researchers to questions about who owned them and buried them and the role of the Church in the silver economy in Viking Age Britain and Ireland.

Archaeologists agree, after studying artifacts from Viking Age hoards, that the Vikings craved silver, using it for display purposes, as a statement of wealth, and as currency.

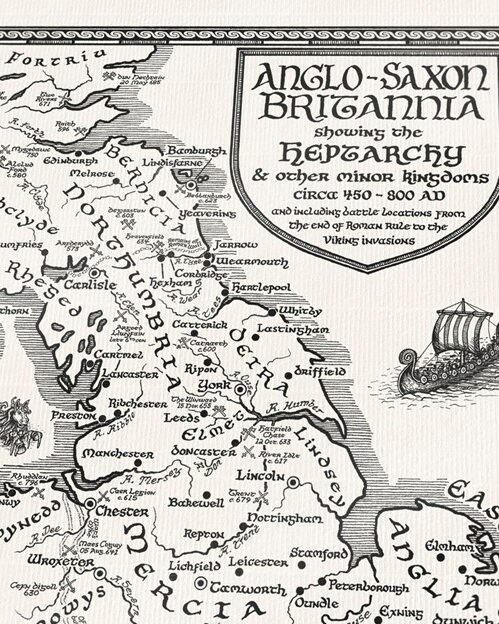

In the four hundred years between the decline of the Roman presence in Britain and the Vikings’ arrival in the late eighth century A.D., silver had been scarce on the island. But when the Scandinavians began to permanently settle in the British Isles and take over the land formerly belonging to Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, they brought huge quantities of silver with them, often acquired through trade with the Islamic caliphates. (Archaeology, 2022 May/June)

Some individuals spend years trying to find a hoard, sometimes getting lucky and discovering artifacts that provide valuable information regarding life in those times. For instance, an amateur treasure hunter on the Isle of Man discovered a Viking Age hoard that contains a 1,000-year-old analog to today’s Bitcoin. In 2014, an amateur metal detectorist went looking for treasure and found a number of silver artifacts buried in a shallow pit on Church of Scotland land. He notified authorities and an archaeological team began to work the site. The Hoard discovered, now known as the Galloway Hoard (see Archaeology, 2022 May/June), dates to about nine hundred, numbers around one hundred artifacts and is the richest, most diverse, and most curious collection of Viking Age artifacts unearthed in Great Britan or Ireland. Simply put, it defies the stereotype of a ‘Viking’ hoard. The hoard was saved for the nation by the National Museums Scotland in 2017 after a major fundraising campaign. Since then, curators and conservators have been working to clean, preserve, and understand the Hoard. The results to date are shown in a new exhibition, Galloway Hoard: Viking-age Treasure, currently on display in Edinburgh.

The Galloway Hoard was buried in layers and separate parcels, which give a rare insight into how the collection was brought together. Silver bullion made up of arm-rings and ingots formed the upper layer of the hoard, separated from the lower layer that lay hidden beneath, disguised by what looked like a natural gravel.

The most common objects in the hoard are silver Hiberno-Scandinavian broad-band arm-rings. Although the arm-rings cannot be dated directly, other hoards containing similar arm-rings also contain coins dating to AD 880-930. This suggests that the Galloway Hoard is Scotland’s earliest Viking Age hoard.

The silver arm bands were made by hammering out carefully measured portions of ingots. Many of the bands in the hoard have never been shaped to be worn, even though they were decorated. Most are flattened and folded, intended as bullion and valued for their weight, like the ingots found with them. Some have been hacked into portions, already used as bullion and ready to be recycled again.

Some of the pieces of bullion are of standardized weights, multiples of a 26.6g unit, corresponding to an ounce of silver in the standardized system. The best evidence for this weight system comes from the Viking Age settlement of Dublin, where many lead weights of this unit have been found. The Galloway Hoard bullion is therefore part of a common silver economy around the Irish Sea.

More silver was recovered from the plough-soil surrounding the hoard. Some pieces may have been displaced from the bullion, but others are from activity on the site. There is some evidence for buildings around the hoard site, which is now legally protected. Further investigation will yield vital information for understanding the context of the hoard.

So many of the artifacts found in the Galloway Hoard were silver that it was assumed to be a Viking hoard. Yet on closer inspection, there were certain objects that forced researchers to question their assumptions. For instance, one object was a gold Anglo-Saxon-style pin shaped like a bird, another was a silver cross decorated with Anglo-Saxon zoomorphic and geometric designs popular in the kingdoms of southern Briton in the ninth century A.D. The cross is decorated in Late Anglo-Saxon style using black niello and gold-leaf. In each of the four arms of the cross are the symbols of the four evangelists who wrote the Gospels of the New Testament, Saint Matthew, Mark (Lion), Luke (Cow), and John (Eagle). Arm rings that were found could be divided into four types and were inscribed using Anglo-Saxon runes (ancient letters). As well as silver bullion, the Galloway Hoard contained an ample collection of brooches, bracelets, glass beads, pendants, curios, heirlooms, and more gold than any other hoard surviving from Viking Age Britain and Ireland.

Within the lower deposit of silver bullion, there are clues pointing to four different owners. There are four intriguing arm-rings inscribed with Anglo-Saxon runes. Some are Old English words that were frequently used as name-elements. A complete Old English name, Egbert, was carved on a hacked arm-ring recovered from the surrounding site. These silver arm-rings are often labelled as ‘Viking’ artefacts, so it is quite unexpected for these runic inscriptions to use Anglo-Saxon rather than Scandinavian runes. By the time these arm-rings were inscribed, in the late ninth or early 10th century AD, Anglo-Saxon runes had been used in Britain for more than four hundred years and had developed different letter forms from Scandinavian runes. The use of these runes in the Galloway Hoard, and the Old English names they represent, hints at more complex identities for the owners and users of this bullion than the simple stereotype of Viking raiders.

The contents of the vessel also include the first collection of Late Anglo-Saxon brooches from Scotland. Disc-brooches are not found in Scotland but are more common in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of southern and eastern Britain. Along with these uncommon brooches, there is a pair of multi-hinged straps placed within the vessel. These straps – elaborate dress accessories – are unique for Anglo-Saxon metalwork.

Within the hoard is the largest collection of Viking Age gold surviving from Britain and Ireland. All of the gold objects are unusual and distinct from one another, coming from distant places and different manufacturing traditions.

A silver vase uncovered was filled with miniature treasures that seem to have been collected over hundreds of years and across thousands of miles. Textiles wrapped around the vase depict Zoroastrian fire altars, winged crowns, and animals such as leopards and tigers, all common motifs associated with the Sasanian Empire, the ruling empire of modern-day Iran from 224 to 651 A.D. Other artifacts are also wrapped in textiles. One is a two-inch tall jar made of rock crystal and gold whose features indicate that it was manufactured in the Roman Empire. The silk in which it as wrapped is thought to have originated in a market along the Eurasian Silk Road.

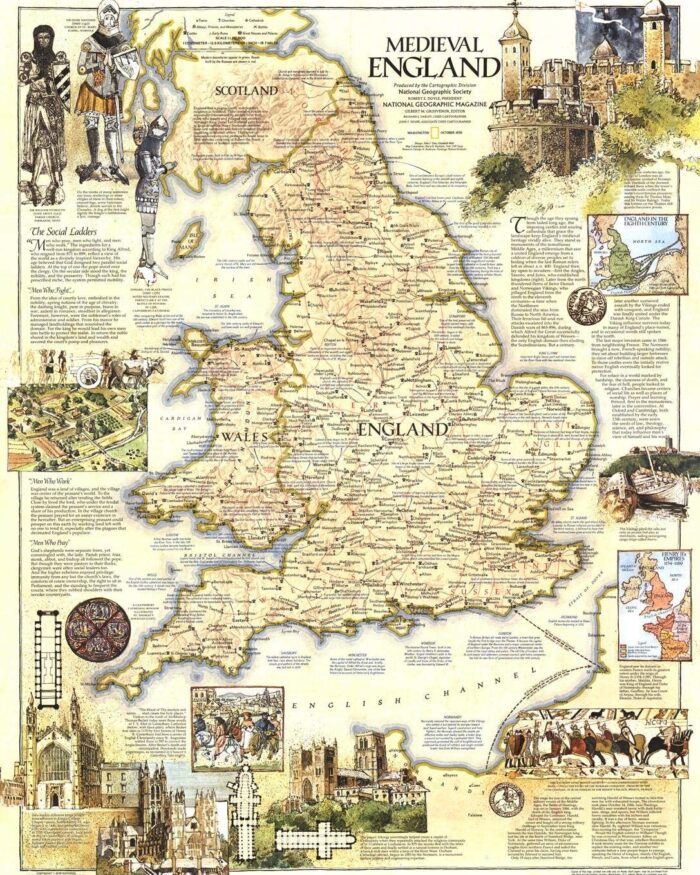

To try to make sense of the Galloway Hoard, researchers regarded Galloway’s unique location at that time.

Around the time the Galloway Hoard was deposited, the medieval kingdom of Scotland was just beginning to take shape to Galloway’s north, while a unified England made up of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms was forming for the first time in southern Britain under Alfred the Great (871-899) and his successors. (Archaeology, 2022 May/June)

Galloway also found itself situated between two Viking kingdoms, one based in Dublin and controlling the Irish Sea and the Scottish west coast, and a group controlling much of northern, central, and eastern Britain. This second territory was known as the Danelaw and its capital was Jorvik or what is now York. Galloway was part of Anglo-Saxon Northumbria but was cut off from other Anglos-Saxon and surrounded by Vikings. The Galloway Hoard reflects this mix of cultures.

When we think of ‘Viking Age’ objects we often imagine swords, shields, ships, and other warlike expressions of material culture. The delicate sophistication of many of the objects in the Galloway Hoard challenges us to see the people of the past as complex individuals just as concerned with aesthetics, amusement, and creativity as many are today. It indicates that the Vikings were not of a single geographical origin or ethnicity. They integrated very quickly into the politics and society of Britain and Ireland, quickly adopting new languages, habits, and customs while also retaining the old. Galloway seems to have stood between the old and new longer than most parts of Scotland. The Galloway Hoard reflects the mix of world views and cultures existing there during the Viking Age.

We will undoubtedly hear more about The Galloway Hoard in the future as the project continues, enabling more detailed analysis and understanding of this complex hoard, including scientific dating of some materials and, it is hoped, identification of some places of origin.