Æthelstan Unites England

Æthelstan (also spelled Athelstan), birth 895 AD/crowned, 924 at age 30/death 939 at age 44/spouse, never married

House: Wessex/Father, King Edward the Elder/Mother, Ecgwynn

Children: None

Reign: King of the Anglo-Saxons, 924-939

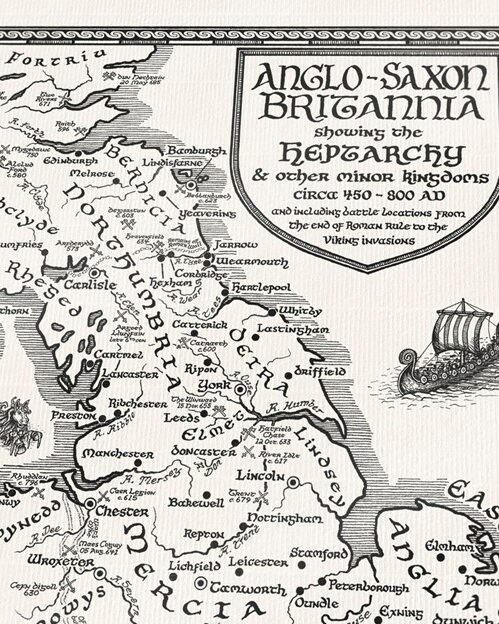

Æthelstan was privileged from birth. Although he was born illegitimate to Edward the Elder and his mistress Ecgwynn, he was well loved by both his father and his grandfather Alfred the Great. Brought up by his aunt, Æthelflaed, Lady of the Mercians, he became a knight at an early age. His mother eventually became queen, which legitimized his right to the throne.

When Æthelstan’s father King Edward died in 924, Æthelstan was not the first in line to succeed; he had an elder brother, Ælfweard. However, Ælfweard died within a fortnight of his father’s death and Æthelstan was crowned king with much pomp and circumstance on September 4, 925 at Kingston-upon-Thames. Æthelstan came to the throne as a seasoned battlefield commander and was very well educated in the ways of war. Following ancient custom, he took possession of his throne standing upon a large rock. The rock still exists, standing outside the Guildhall at Kingston-upon-Thames, with a silver penny from the reign of each Saxon king set into its plinth (base).

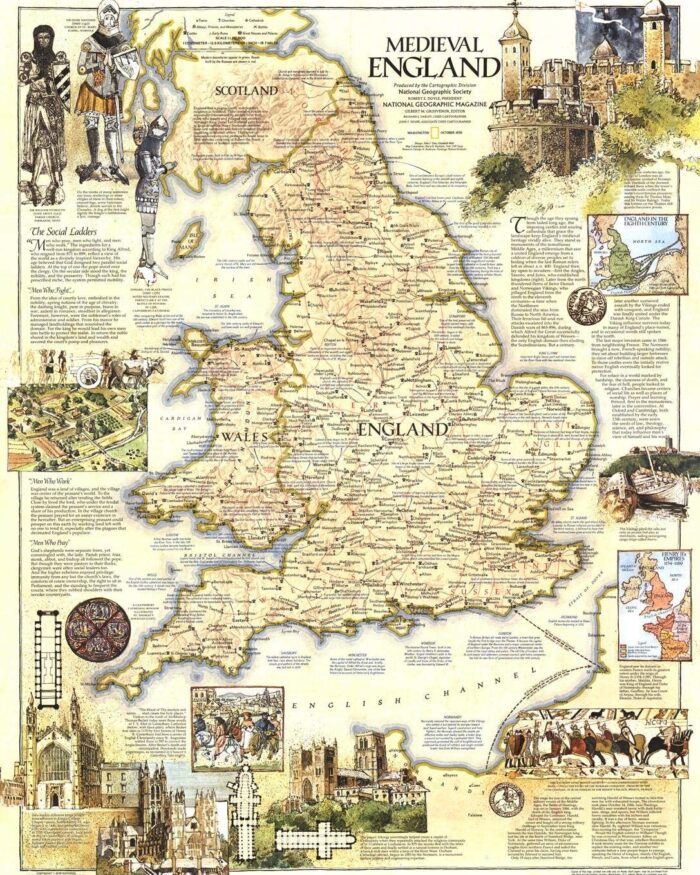

Æthelstan spent the first couple of years of his reign consolidating his rule and centralizing his power over the other English kingdoms. He built a huge multi-ethnic army (one that for the first time was drawn from all the corners of the realm) and an equally strong fleet. His greatest military victory took place in 937 at the Battle of Brunanburh. At that time, Olaf Guthfrithson formed an alliance with Constantine II, who ruled Scotland, and Owain of Strathclyde to invade England. Olaf took Æthelstan by surprise, yet still Æthelstan triumphed. The battle was renowned for being one of the greatest to ever take place on British soil and was the largest of this period. It resulted in Æthelstan becoming the first English king to rule over a centralized, unified state encompassing the entirety of modern-day England.

Æthelstan was a key figure in the development of the idea of the English king as Christian hero. This idea was employed to significant effect by all of the West Saxon kings in creating a unified kingdom of England. Both his charters and the silver coinage he issued through strictly controlled regional mints bore the proud title Rex totius Britanniae (“King of all Britain”).

The successes and popularity of Æthelstan ushered in a period known as the “Imperial Phase” (925-975) or the “Golden Age of the Anglo-Saxons.” Welsh and Scottish kings attended English court alongside English earls and great advances were made in law making, education, and the arts. Not only did King Æthelstan centralize government and continue the legal reforms of his grandfather King Alfred he also became a global monarch, accepting into his court princes from all over Europe and establishing England as a power in Europe by arranging political marriages for many of his sisters to foreign kings. Legend has it that he sent two sisters to Otto I, the Holy Roman Emperor, telling him to choose which he fancied. Otto chose Eadgyth (also spelled Edith or Ædgyth) a woman “of pure noble countenance, graceful character and truly royal appearance” according to a female historian at that time. He married another sister to Sihtric Cáech (meaning the ‘Squinty’), the Viking King of Yorvik (York). The marriage took place at Tamworth and resulted in Sihtric acknowledging Æthelstan as over-king and converting to Christianity. Yet another sister, Edgifu, became Queen of France through her marriage to Charles the Simple while a fourth married Viking Egil Skallagrimson, the subject of an Icelandic saga. A fifth sister’s marriage forged a political alliance with Alan II of Brittany.

King Æthelstan was a pious ruler. Not only did he oversee the translation of the Bible into English, he founded many monasteries such as the Abbey of St. John at Beverley and was a collector and generous bestower of holy relics. For instance, in 926, according to 12th century English historian William of Malmesbury, he agreed to give his half-sister, Eadhild, in marriage to Hugh, Duke of the Franks, in return for an enormous quantity of gifts such as a crown of solid gold; the sword of Constantine the Great, (which had fragments of the cross including a nail set in crystal in the hilt); Charlemagne’s lance (which was said to have pierced the side of Jesus); and a piece of the Crown of Thorns. Æthelstan gave these relics to Malmesbury Abbey. He gave away more bizarre relics like the head of St. Branwaladr to the Abbey of Milton in Dorset, where it was worshipped until the Reformation.

On the economic front, Æthelstan established a formal organization for masons which may have led to Freemasonry in England. He encouraged the establishment of burhs where trade would become concentrated. This discouraged fraud and laid the foundation of a rural economy based on the market town. He reformed the currency which had become badly debased.

One myth surrounding King Æthelstan concerns another brother of his named Edwin. The story goes that fearing a challenge to the throne, Æthelstan banished Edwin by setting him adrift in a small boat with no provisions. Legend maintains that Edwin drowned himself rather than face starvation. Regretting the whole affair, Æthelstan later turned to charitable efforts, using a portion of the income from each of his estates to support the poor, and reforming the law to make it fairer and more lenient on young offenders.

King Æthelstan ruled for fifteen years and died at forty-four leaving England one of the richest countries in the world. Instead of being buried beside his father and grandfather at Winchester, a city that had opposed his rule, he chose to be interred at Malmesbury Abbey, the resting place of those in his family who had fought alongside him at the Battle of Brunanburh. His skeleton was lost in the turmoil of the Reformation, but a 15th-century effigy and tomb mark his burial place.

The 12th-century chronicler William of Malmesbury wrote that no one more just or more learned ever governed the kingdom. It is a verdict shared by modern historians, who generally regard Æthelstan as the one Saxon king who can be reasonably compared to his grandfather Alfred the Great. Not until Edward I three and a half centuries later would an English king lead his armies so far north or coerce the rulers of both Wales and Scotland to attend assemblies in southern England.

Æthelstan presenting a book to St Cuthbert

The Coronation Stone at Kingston-upon-Thames