Sutton Hoo Discoveries

In 1938, Mrs. Edith Pretty, a widow and daughter of a wealthy industrialist, contacted the Ipswich Museum to ask if there were anyone available to investigate a gigantic mound of earth on her Sutton Hoo, Suffolk, UK property. The museum sent out a self-taught archaeologist named Basil Brown. Assisted by Mrs. Pretty’s gardener and gamekeeper, Mr. Brown was the first to excavate the site, which was ultimately taken over by the British government. Over time, it came to include fifteen mounds of various sizes and became the richest archaeological find in British history and one of the greatest archaeological finds of all time.

Mr. Brown’s work on that first mound uncovered the impression of a ship which had long since rotted away. Then came the burial chamber which held weapons, golden garnet jewelry, silver, drinking horns, drinking vessels, shoes, and buckles among other ancient treasures from the early Middle Ages. In 1939, the excavation continuing under the aegis of the British government, newly discovered rusted pieces of an iron helmet were painstakingly put back together. The find included everything you could wish for in trying to determine what life was like for an Anglo-Saxon king during the Medieval Ages.

Historians and archaeologists were unable to positively identify the individual buried with so much treasure because there was nothing left of the person laid to rest there. The ship buried in the ground collected so much acidic liquid that the body dissolved over the years leaving only a few chemical traces behind. Yet, in 1939, the artifacts gave strong enough clues that the British Museum’s Thomas Kendrick identified the burial site as that of King Rædwald, ruler of East Anglia from about 600 to 620.

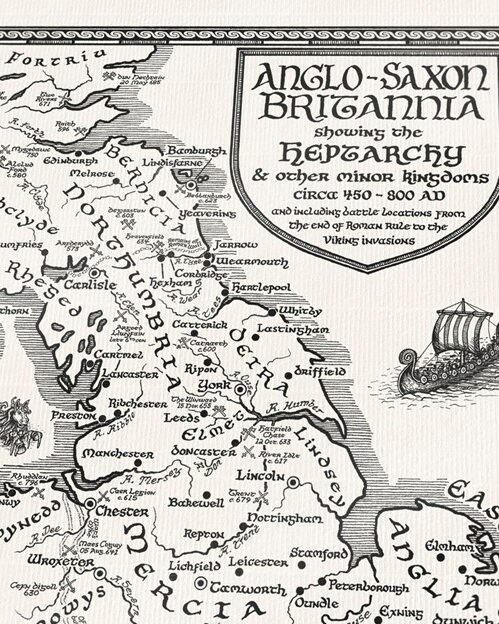

Almost all we know about king Rædwald comes from The Ecclesiastical History of English People written in the 8th century by the Anglo-Saxon monk known as the Venerable Bede. The Venerable Bede writes of King Rædwald as a man who ruled over other local kings and kingdoms that were not his own. He referred to him as a ‘bretwalda’ (also spelled Brytenwalda, Bretenanwealda, or Brytenweald) or overlord of not only his own kingdom but others as well. Venerable Bede refers not only to Rædwald of East Anglia as a bretwalda, but also Ælle of Sussex, a powerful 5th-Century warrior who is known, among other things, to have seized a Saxon Shore fort near Pevensey; Æthelberht of Kent; Oswiu of Northumbria; Penda of Mercia; Offa of Mercia; Egbert of Wessex; Alfred (the Great) of Wessex; and Æthelstan of Wessex.

The riches found at Sutton Hoo provide a glimpse into the lives of bretwalda in the seventh century. First of all, they were incredibly rich, so rich that they could be buried among their most valuable possessions. For instance, found at Sutton Hoo was a huge golden belt buckle worth at that time 300 Anglo-Saxon shillings. The law codes of that time tell us that this was exactly the life price of a nobleman; in other words, if one nobleman killed another, it was the debt he had to pay. We can assume, to deter nobleman killing each other, this was an enormous sum of money.

No crown was found at Sutton Hoo. What was found were the remnants of the sword and helmet which defined the monarchy at that time. Unlike today, warfare was an aristocratic occupation and if a battle were lost, the casualties among the wealthy and powerful were high. Archaeologists believe the helmet found at Sutton Hoo was made in England but a closer look at the images led to their links to Scandinavian mythology as well as Roman influence. The structure of it is based on a Roman parade helmet.

The discoveries at Sutton Hoo lend support to historians’ affirmations that local kings were not part of a royal line but rather successful warriors that established their dynasties in Britain. Many of them migrated not only from the east but from Norway and Sweden as well. Burial artifacts from Sutton Hoo also represent the mix of pagan and Christian beliefs held by rulers such as Rædwald. Although it appeared to be a pagan burial with provision made for pagan afterlife, two silver baptismal spoons with a Greek inscription +SAULOS or +PAULOS were also included. The helmet does not contain any of the protecting Christian symbolism found on helmets from the 8th century found in York, but rather the safeguarding totemic and mythological animal images represented in pagan beliefs.