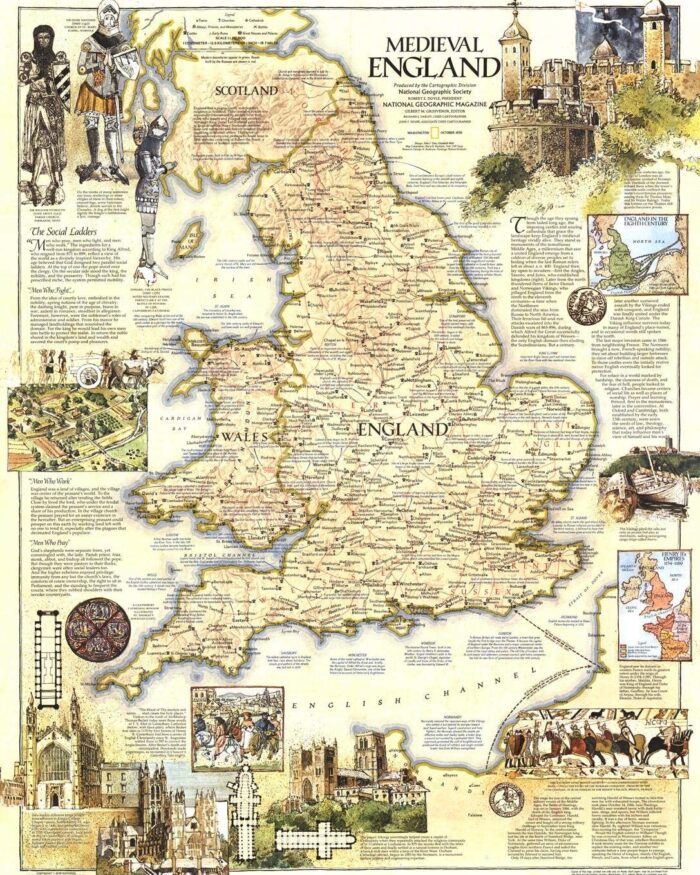

Oswiu and Offa: Early Bretwalda

Let’s take a closer look at two of the bretwalda or ‘over-kings’ not yet described in our narrative. They are Oswiu of Northumbria and Offa of Mercia. Both exemplify the way in which warriors expanded their authority in the seventh and eighth centuries.

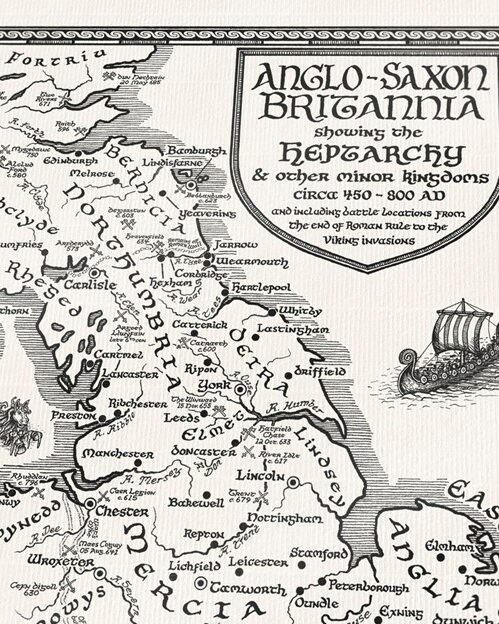

Oswiu (613-670) was the son of Æthelfrith, king of Bernicia and Deira which together formed Northumbria. After his father’s death Oswiu and his half-brother fled to Iona on the west coast of Scotland but he returned and gained control of Northumbria in 655 when his forces overcame those of Penda (see Localized Leadership) in the Battle of the Winaed near Leeds in modern west Yorkshire. He then became the ‘Bretwalda’ of Northumbria.

Kingdom of Northumbria c. 604-954 CE) in northeast Britain

Source: World History Encyclopedia, Kingdom of Northumbria

Oswiu was a staunch Christian who had been raised in the Celtic tradition and his wife, Eanfled had been educated in the traditions of the Roman church. In 663/664 Oswiu helped reconcile differences in modes of worship between the Celtic churches and the Roman Catholic church at the Synod of Whitby (see picture below).

A scribe, thought to be Bede, who described the Synod of Whitby in the early 8th century.

Source: English Heritage: How the Synod of Whitby Settled the Date of Easter

Whitby Abbey and the headland seen from West Cliff.

The headland may have been the site of a Roman signal station in the 3rd century AD.

Source: Facebook and History of Whitby Abbey

Whitby Abbey’s ruins are located in the city of the same name in North Yorkshire on the north-eastern coast of England. In 664, the abbey hosted Whitby’s synod, during which King Oswiu declared that the church of Northumbria would adopt the calculation of Easter and the rite of the tonsure of the Roman Church, abandoning the uses and customs of Celtic Christianity for the dictates and doctrines of the Church of Rome. The Abbey has a long history as a Benedictine monastery and pilgrimage site. Its Gothic architecture and coastal views provided the setting for Bram Stoker’s Dracula when he arrived in England.

Oswiu ruled from 655 to 670 and his reign of power exemplified three important themes of kingships at that time: surviving exile to rule, marrying to gain support of other leaders, and using religion to gain dominance. Upon his death he was succeeded by his son Ecgfrith.

Offa and his retinue kneeling at the Holy Sepulchre.

Like Oswiu, Offa (?-796) was both a strong and enduring king, as well as being renowned for his overwhelming lust for power. Offa was described by Alfred the Great’s biographer and ninth-century monk Asser as ‘a vigorous king who terrified all the neighbouring kings and provinces around him’.

A member of an ancient Mercian ruling family, Offa seized power in the civil war that followed the murder of his cousin, King Aethelbald of Mercia (reigned 716–757) (not to be confused with King Æthelbald of Wessex). By brutely suppressing resistance from several small kingdoms in and around Mercia, he created a single state covering most of England south of modern Yorkshire. The lesser kings of this region paid him homage, and he married his daughters to the rulers of Wessex and Northumbria.

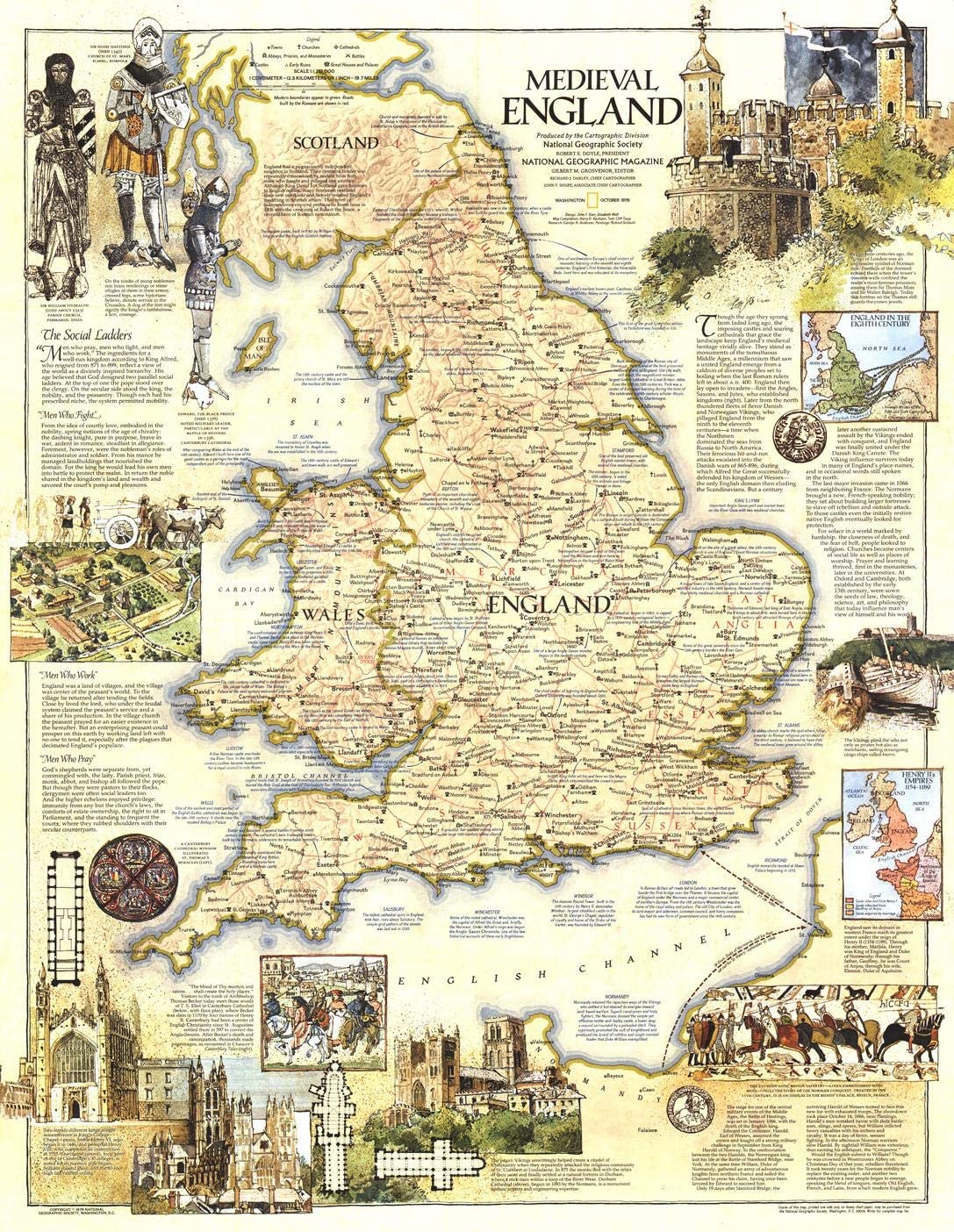

Map of Mercian hegemony c. 796. Source: Offa of Mercia

Old map of England, showing the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms.

(Photo: mikroman6 via Getty Images)

Source: Who Was King Offa of Mercia and What Did He Do?

As ruler of Mercia from 757 to 796, Offa brought southern England to the highest level of political unification it had yet achieved in the Anglo-Saxon period. He also formed ties with rulers on the European continent. Charlemagne, king of the Franks, quarreled with Offa, but the two rulers concluded a commercial treaty in 796. In addition, Offa maintained a friendly relationship with Pope Adrian I, who was allowed to increase his control over the English church, while acceding to Offa’s request for the creation of an archbishopric of Lichfield. This remarkable, if temporary, change in church organization freed the Mercian church from the authority of the archbishop of Canterbury, who was seated among Offa’s enemies in the kingdom of Kent.

An impressive memorial to Offa’s power survives in the great earthwork known as Offa’s Dyke, which he had constructed between Mercia and the Welsh settlements to the west. He built this formidable 26 foot high, 80-plus mile earth dyke to defend those who lived in England from those who lived in Wales.

Offa’s Dyke was built in the 8th century at a time when Britain was not a single state but a number of small kingdoms. The Ceiriog Valley was part of Powys which had included much of modern Shropshire and Cheshire but those areas had been taken by the kingdom of Mercia. The kings of Powys fought to regain their lost territory by attacking the Mercian settlements. In response, Offa, king of Mercia, commanded the building of what was to be the longest bank and ditch in Britain to mark the boundary between Powys and other Britonic kingdoms to the south, and Mercia.

3 Offa’s Dyke (northeastwalestrails.com)

Source: The Offa’s Dyke Collaboratory

Source: Offa’s Dyke Path

Heading down into Redbrook with fantastic views over the River Wye towards the southern end of the trail.

Source: Offa’s Dyke Path National Trail – The Backpacker’s Guide

The 177-mile Offa’s Dyke Path runs from Chepstow in South Wales to Prestatyn in North Wales.

Source: James Osmond/Getty Images)

The dyke in question is Offa’s Dyke, a 1,200-year-old earthwork that spans the length of the England-Wales border. Like Hadrian’s Wall, The Great Wall of China (and, come to think of it, The Wall from Game of Thrones), Offa’s Dyke divided lands. It marked a threshold between Anglo-Saxons and Celts, plains and mountains, life and death, ears and no ears.

But unlike Hadrian’s Wall and the Great Wall of China, there is not much of it left to see. Today, dandelions and nettles sprout where battlements once rose. Generations of sheep have trodden on the dyke. It is now only a small bump – a hiccup in the fields. If an invading army were to cross it today, the best you could hope for is that they trip over the dyke and go home with a sprained ankle. Or maybe a nosebleed. Source: Offa’s Dyke: Britain’s ‘No Man’s Land’

“One of the most enduring legacies of the reign of Offa, Anglo-Saxon king of Mercia was his reforms of the system of coinage. Taking his cue from the French coins of the Carolingian dynasty, Offa’s coins were beautifully and intricately designed and carried the king’s name and, for the first time, that of the moneyer, the man from whose mint the coins emanated. Indeed it was said that his coins displayed ‘a delicacy of execution which is unique in the whole history of the Anglo-Saxon coinage.’ One stand out aspect of his coins was that his wife Cynethryth was also featured upon them, becoming the only Anglo-Saxon queen to have her name depicted on coinage.

Portrait penny of Cynethryth, minted by Eoba at Canterbury

Oswiu and Ossa are just two of the Bretwaldas or ‘overkings’ of Anglo-Saxon England during the early Medieval Ages. Others include Ælle of Sussex, Ceawlin of Wessex, Æthelberht of Kent, Rædwald of East Anglia (see Sutton Hoo Discoveries), Edwin of Deira, Oswald of Northumbria, Egbert of Wessex (see Egbert: Wessex Rises to Power), and Alfred the Great of Wessex (see Alfred the Great Saves England).

March 15, 2025 Entry on Facebook

King Offa of Mercia rides with his retinue past Tamworth Castle with its statue of Æthelflæd.

These are re-enactors from Regia Anglorum and Thegns of Mercia commemorating his issuing of a charter from the town in 781.