Aurelianus and Arthur: Warrior Legends

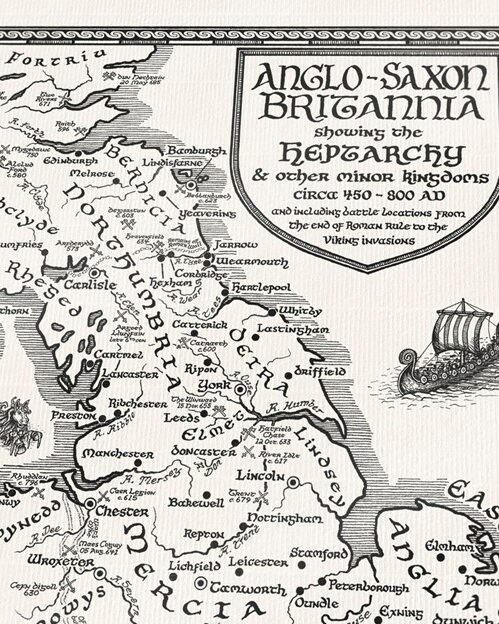

Ambrosius Aurelianus is one of the few people that Gildas identifies by name in his sermon De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae, and the only one named from the 5th century. De Excidio is considered the oldest extant British document about the so-called Arthurian period of Sub-Roman Britain. Gildas was both Celtic and Christian and he may well have created Ambrosius Aurelianus as an example of what he believed a great king should be: a Celtic war leader of Roman ancestry fighting tirelessly to rid Britain of Saxon invaders from what are now Germany and Denmark.

| Both Ambrosius and Arthur are representatives of what historians like Gilda and Nennius considered the ‘last of the Romans’: those who embodied the highest values and greatest virtues of ancient Roman civilization at different times in history. Gildas exalts Ambrosius as a true Christian hero as does Nennius with Arthur. Although to date there is no tangible evidence that Ambrosius and Arthur existed, they may very well provide clues to how some individuals felt about the changes to Britain’s population. These individuals mourned Britain of the past and feared for their future. They viewed newly arrived Saxon immigrants as threats and longed for military superheroes to “make Britain great again.” |

Gildas does not tell us whether or not Ambrosius was a king. He could have just been a military commander. Later tradition does call him a king, though, and there is nothing in Gildas’ words that makes that unlikely or improbable. He tells us that Ambrosius’ parents had “worn the purple,” but that they had died during the strife of that era. In later years, the Venerable Bede continues to write about Ambrosius and dates his career from 470 to 491.

Ambrosius is mentioned as the leader of two great fifth century battles: the Battle of Guoloph or Wallop (sometime in the late 430s) and the Battle of Badon. The Battle of Guoloph took place in what is now Nether Wallop, 15 kilometers southeast of Amesbury, in the district of Test Valley, northeastern Hampshire. The battle pitted a Briton alliance against invading Jutes and Saxons. The Britons were victorious. There is uncertainty as to the date and location of the Battle of Mount Badon and what makes things even stickier and trickier is that Ambrosuis in some records morphs into this guy here, who becomes WAY more popular.

The dashing King Arthur, the ‘Gold Standard of Warriors’

There is much controversy over just when Arthur was first created but we do know that by the 9th century the Historia Brittonum, compiled by the Welsh historian Nennius, refers to him as the “Dux Bellorum” (war chief) leading “the Kings of Britain” and not only with winning the decisive battle at Mount Badon, but eleven other battles as well. Nennius’ list of battles is drawn from Welsh poetry and they took place in so many different times and places that it would have been impossible for one man to have participated in all of them.

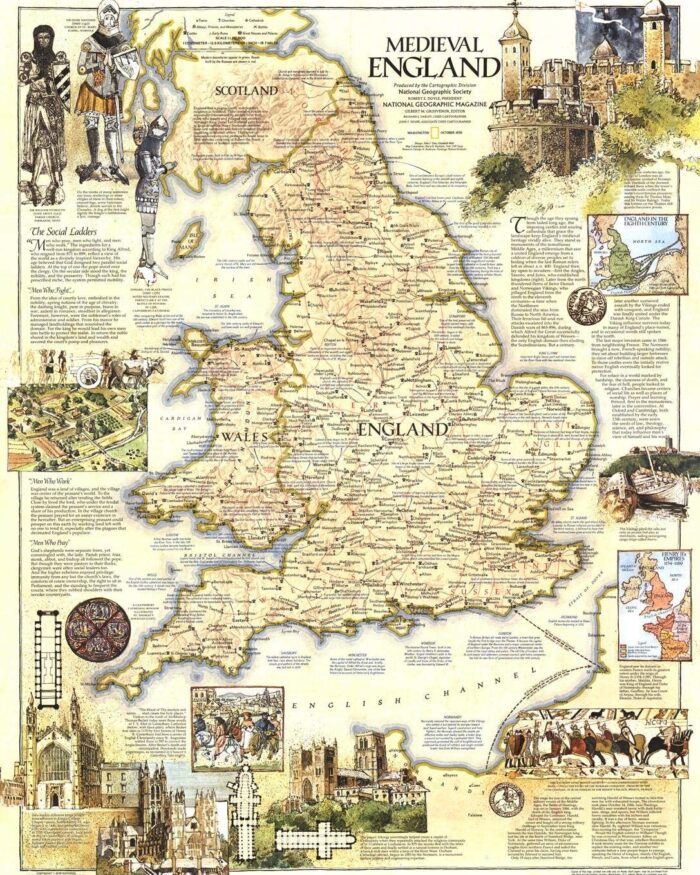

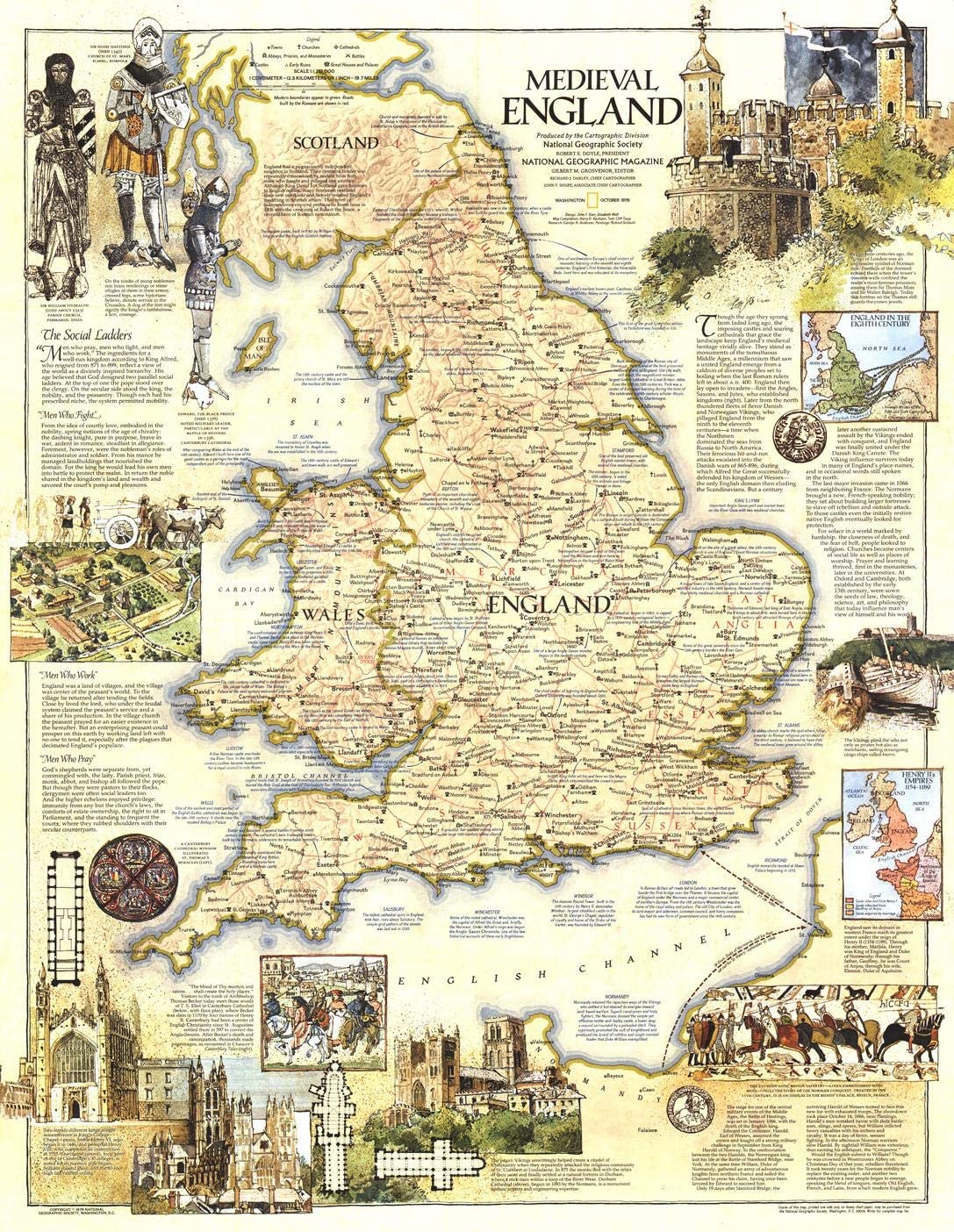

Later Welsh writers drew on Nennius’ work, and Arthur’s fame spread beyond Wales and the Celtic world, particularly after the Norman conquest of 1066 connected England to northern France. In 1130, Geoffrey of Monmouth, using Celtic and Latin sources, spent years creating a lengthy chronicle, the History of the Kings of Britain, Blending myth, legend, and perhaps some truth Geoffrey placed Arthur as the focus of this tome. King Arthur ruled Caerleon (castle) with his magical sword Caledfwlch aided by a wise counselor named Merlin based on the Celtic bard Myrrdin. Geoffrey’s History was soon translated from Latin to French by the poet Wace around 1155. Wace added another part of Arthurian lore to Geoffrey’s sword, castle and wizard: the Round Table. He wrote that Arthur had the table constructed so that all sitting there would be equals. After reading Wace’s translation, another French poet, Chretien de Troyes wrote a series of romances introducing tales of individual knights like Lancelot and Gawain and mixed elements of romance with adventures. Numerous adaptations in French and other languages followed and Caerleon became Camelot and Caledfwlch became Excalibur. In the 15th century Sir Thomas Mallory fused the Arthurian stories in Le Morte D’Arthur. Like many of the leaders real and imaginary, the many versions of Arthur reflect the culture and concerns of their authors and audiences.

|  |

| Illustration of King Arthur in battle, 13th century (via pocketmags.com) | Illustration of King Arthur fighting the Saxons from the Rochefoucauld Grail manuscript, 14th century (via the Independent) |

There are plenty of places to visit in Britain that are associated with the legendary King Arthur, among them the Great Hall of Winchester Castle where the famous Round table can be found and Tintagel Castle in Cornwall the birthplace of King Arthur.

The Great Hall with Westgate Museum

Thomas Malory, the 15th century author of Le Morte d’Arthur, identified Winchester as the site of Camelot. Here, dominating The Great Hall, is the iconic Round Table – famously linked to the ancient legends of King Arthur and his Knights

Tintagel was a stronghold for early medieval rulers. It may have been memories of this seat of Cornish kings that inspired Geoffrey of Monmouth to name it as the place where King Arthur was conceived. It was almost certainly this link to the literary hero that inspired Richard, Earl of Cornwall, to build his cliff-top castle here. The brooding figure on the island – Gallos (meaning ‘power’ in Cornish) – is a life-sized bronze sculpture inspired by the legend of King Arthur and Tintagel’s royal past.